July of 2020 was marked by a scandal in the Ukrainian public sphere seemingly related to the External independent evaluation (ZNO) history exam. ZNO-related scandals happen on a regular basis, however, this one was especially bitter.

July of 2020 was marked by a scandal in the Ukrainian public sphere seemingly related to the External independent evaluation (ZNO) history exam. ZNO-related scandals happen on a regular basis, however, this one was especially bitter. Graduates of one of the Kyiv schools recorded a video featuring their discontent regarding ZNO questions on Crimean Tatar historical figures, ugly hate speech about ZNO in general, the Quality of Education Centre in particular and… Crimean Tatars.

Why “seemingly related”? Because in fact the problem is much deeper and more complex. The essential question is how we teach children history, what we want to teach them, why we do it in general, and what mistakes we make along the way. Don’t we become those wise people who lose sight of the forest for the trees?

The discourse behind the video

This video is an example of hate speech and an emphatic demonstration that most often its roots are ignorance and lack of critical thinking. The children in the video did not know the answers to the questions and were looking for someone to blame (for sure, not themselves)—the historical personalities mentioned in the question, their ethnicity, those who wrote the test, and so on. Psychologist Olena Ratynska commented to ‘Channel 5’ that shifting responsibility to others is typical for teenagers, but at the same time pointed out that the children's behavior in the video is the first sign of bullying (hateful behavior). “One aggressive child offers an object for bullying to other children.” That is true, the girl who was recording the video was visibly inciting others. But does it make her responsible for all the other teenagers? For the whole school? For parents? For society? Teenagers used the vocabulary and figures of speech of physical dominance and violence that ‘were in bloom’ in public discourse this summer. We heard them from bloggers, deputies, and other ‘opinion leaders’. They did not bear responsibility—first of all, a reputational one—for such vocabulary and language of discrimination, and therefore legitimised this style of communication. It was a shame that no one interrupted this hate speech in the video. It was a shame but it was predictable because the teenage age requires being accepted by the group while contradicting a group requires great courage and critical thinking.

Unfortunately, the media were not brave and critical enough either. On July 10-12, Glavkom, Unian, Channel 5, Gazeta.ua, TSN, and Detector Media covered the event, some of them gave a balanced view, others were enjoying the scandal. Every news story ended with the message that the head of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar people—Refat Chubarov—suggested that the conflict is over since some of the students “found the strength to apologise” and invited them to the Mejlis office, where Mustafa Dzhemilev would present them books on the history and culture of Crimea and the Crimean Tatar people.

However, only two media—Ukrinform and Krym.Realii—published the information on this visit of the students who apologised, their parents, school representatives, on their dialogue which allowed everyone to speak up. In order to find this out, they had to contact Refat Chubarov directly, since the media that had covered the scandal saw no need in covering how it was resolved. In fact, the culture of dialogue and conflict resolution itself was left out of the equation.

To be honest, it was not the situation with the children that frightened me the most. They may be sorry and draw conclusions. The most terrifying thing was that many adults expressed polar opinions on social media. While some wrote “what did they say?”, “why should Crimean Tatars be present in Ukrainian history?”, “why are Crimean Tatar dissidents present in the tests while Ukrainian nationalists are not?”, others demanded that these children should never enter universities or should even be expelled from Ukraine.

Healthy patriotism allows people not to love their homeland blindly and embrace its imperfections. History is not a perfect story featuring angels but it is important to talk about it with children, teach them critical thinking and nurture their active citizenship. Confusing xenophobia with patriotism is as dangerous as direct discrimination. The tendency to justify that someone has suffered more or saying “why are you not writing here that someone (insert a relevant group) has also suffered” is flawed thinking that comes up constantly. You will hear this kind of argumentation strategies (which are, in fact, prejudices) when it is “not the time” to discuss the rights of some group because there is war, recession, etc. (insert a reason as appropriate), that you should not be afraid of coronavirus because tuberculosis and cancer kill many more people.

What we teach while teaching history and why?

It is unlikely that we can re-educate “people on the Internet", but hopefully we can draw conclusions about the educational process of today's school students. It is important to teach critical thinking from the school years. From the point of view of goal-setting, the situation is not bad at all. The State Standard of Basic and Complete General Secondary Education is a document that describes in detail what we teach (the content of education) and why we teach it (what we want children to know/be able to do).

Here is an excerpt on the state requirements for the historical component of education, the content of which is historical epochs:

“to know and understand the essence of history as a process, science and living memory, possibility of coexistence of different views regarding one historical event of world history and Ukrainian history, the role of Ukraine in the modern world, characteristic features, peculiarities, significance, and consequences of events, phenomena and processes in the history of an epoch, to be able to use historical events to explain phenomena and processes, to get information on history independently from different sources…”.

In addition, after high school children should know what politics, democracy, and civil society are:

“to know and understand the essence and structure of society, the political system and power, features and characteristics of a multicultural and civil society, forms of participation of citizens in the life of the society and the state... to review political systems and regimes, the role of the political elite, activities of local government, attributes of civil society, and the role of mass media”.

It would be great to live in a society where people have acquired this knowledge at least after university (let alone after school), right? What is the problem then? If we’ve so beautifully outlined what we teach and we know why. How does it happen that the case at the beginning of this article actually contradicts every word in these two quotes above? I dare say that developing everything that’s written there requires experimenting with formats of teaching that teachers simply don't have time for because of time-consuming preparation for the External Independent Evaluation, while parents and children have a distorted motivation (only the test results matter). If the names of Crimean Tatar dissidents were more than just names in a textbook, if those children had done a research project by interviewing victims of deportation or the annexation of Crimea, then perhaps those terrible words would not have been said? Perhaps it is worth introducing interdisciplinary courses on literature and history, on cinema and history in order to be able to discuss not only the artistic conflicts of the text but also its cultural conflicts. If we want history to teach dialogue, critical thinking, and conclusion-making, why don't we teach history this way?

I would like to refer you to Most Likely to Succeed: Preparing Our Kids for the Innovation Era by Tony Wagner and Ted Dintersmith [1], a book which analyses in detail the crisis of higher education, the gap between the 21st-century skills needed by university graduates in the workplace and what they are taught. One of the authors’ main points is that the problem is standardised tests. They don't assess real knowledge, but the algorithm for what can be assessed in a test format: dates, names, and correlations. There’s zero creativity as a result.

We teach history at school in a way as if the 20th century gave us only two world wars and the revolution of 1917. What about the history of everyday life, oral history, the history of cultures of remembrance, the history of women (women's history), and so on?

I would like to illustrate how we can apply the above-mentioned ideas in practice.

Interdisciplinary approach of introducing the culture of remembrance. The case of the National Centre “Junior Academy of Sciences of Ukraine”

Like many other educational institutions, the National Center “Junior Academy of Sciences of Ukraine” organises annual summer schools for school students. The philosophy course is aimed at teaching children academic philosophy research skills, giving them an overview of philosophy disciplines, teaching them to work with sources and write well-thought essays. This year’s summer school was titled “The Cultures of Remembrance” and was held online on July 20-24. New challenges were added to the above-mentioned tasks: giving children tools to comprehend the complex world they have faced (the youngsters have witnessed the revolution, annexation, war, and pandemic); reviving the online format—since we’re no longer limited by geography, it was possible to invite the best speakers in Ukraine on the topic. Also, the online format allowed the participation of children from all around the country, therefore experience exchange and communication play a great role in teaching empathy and tolerance.

The summer school’s audience included 102 participants from Volyn, Dnipropetrovsk, Donetsk, Zakarpattia, Kyiv, Kirovohrad and Lviv oblasts, and the city of Kyiv. The age of participants was a big surprise: it was between the 7th grade and graduates.

The summer school name “Cultures of Remembrance” captured the mix of cultural studies, philosophy, and history. The idea was to use an interdisciplinary approach in order to give children the tools to communicate complex issues, to give understanding that a culture of remembrance is something that needs to be developed because complex issues have no simple answers. Since history should be taught not only and not so much through lessons and textbook paragraphs, but by giving the opportunity to feel and to experience the difficult questions and themes, we posed the following cross-cutting questions to the audience: how do we learn about the past? How do we, people of the modern age, see history—is it created by documents and influential people alone? Perhaps, the experiences of “small people” who witness history matter and then shape the memory of individuals, families, communities, societies, and nations? Teaching the culture of remembrance to children is important in order to shape their ability of a scholarly view of history, the skill not to drown in emotions, but to learn to own them and give empathy, to learn to see a wider picture.

Much emphasis was put on students’ individual work with sources: scientific articles, source materials, both documentaries, and popular fiction films, science fantasy.

When inviting lecturers we had pedagogical hypotheses regarding aspects of teaching to the new generation, and we got them confirmed. Today’s teenagers appreciate authenticity and success but not authorities and conventionalities. The invited lecturers are top speakers who often conduct online lectures and are enthusiastic about what they do: Orysia Bila (chairperson of the Philosophy Department of Ukrainian Catholic University), Anton Drobovych (head of the Ukrainian Institute of National Memory), Yuliia Kovalenko (film critic and programmer of the Docudays UA International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival) and others. The emotional component and individual experience are also an important part of learning. We invited participants to search for arguments, explore and acquire new research methodologies. It offered more academic freedom, the courage to discuss complex topics with children, and knowledge that is not given but acquired together.

O. Bila’s lectures on historical memory and A. Drobovych’s lecture on national memory within the topic “Historical Memory” were held in the format of dialogue with students. Both lecturers relied upon a critical perception of history, and not dogmatism. Such a strategy was well accepted by children. Dialogue alone can help form a critical attitude to history. This is also the way to form a civic position and civic engagement. The debate is important for both learning history and teaching any humanitarian subject.

Within the topic “The role of art in creating cultures of remembrance,” lecturers were trying to present how art can help to construct a culture of remembrance and reconciliation. The potential of documentary cinema for shaping the culture of remembrance was a real discovery for participants.

Lecturers were surprised that the students not only attended the Docudays festival online but even volunteered at the event. It was a joyful discovery since it means the children are socially active and do care about what is happening in the world. The Ukrainian documentary cinema is on the rise, the screenings are successful, so it is an important practice to learn to analyse films, to compare one’s conclusions with cinema reviews and one’s memories with the author’s view (within the summer school the students were invited to watch Varta1, Lviv, Ukraine). Our contemporary times require us to broaden the sources that can help us study history. Documentaries, fiction films, novels, graphic novels, contemporary art installations, popular culture pieces in general—all of them can help to understand history.

For example, the topic of colonialism was explored by comparing a fragment from the novel American Gods by Neil Gaiman with the interpretation of slave-trading in the eponymous series. Kateryna Honcharenko, a senior lecturer at the National Pedagogical Dragomanov University, explained how artists treated the complex topics of Holocaust and war by using unexpected formats like installations and graphic novels.

The final task of the summer school was to reflect on the topic of historical events the participants have witnessed. We received many good essays, however, some of them overwhelmed us. Two weeks after the scandalous situation with the video, at the final session of our summer school, Anhelina Driomova was reading us her essay,

“Some 7 years ago I often heard from adults strange and unclear words like ‘annexation’, ‘occupation’, ‘revolution’, and another word, ‘war’, which was already clear at that time. Yes, for someone 7 years can be endless: one can forget, wipe it from memory, become indifferent... But I remember everything as if it was yesterday. I remember how my family was forced to leave our hometown, our homeland, our Vatan [2], and go to Kyiv...

It seems as if everything around is obscured by the thick fog of unspoken words, everything is like some kind of coma, everything is neither new nor how it used to be. Nowadays I realise that I was a witness of a real historical event…

No, I’ve already been a witness of a historical event. I watched the Falcon Dragon-9 launch live. But as for the annexation of Crimea, I saw it with my own eyes. Those were the days when adults tried to explain in simple words what was happening (they did not understand it either). Now that I understand a lot and think about those days, I have very different—often controversial—feelings. On the one hand, it was a kind of military grip—wow, a real historical event was happening before my eyes, I will have something to tell my descendants! On the other hand, now I’ve got a new motivation to study history because not everyone in our country knows about Oleshky Sich in Crimea and says with certainty that “Crimea is Russia”.

I do care whose Crimea is. I do care about our land, I do care what happens, is happening, and will happen on this land. In many years, when history textbooks put the events of the year 2014 in black and white, I will definitely explain everything to my children. History lives within us. History is alive until we and our memory are alive.

Anhelina Driomova, 9th grade, Kyiv, training and educational complex №157

This summer school granted us a great pedagogical discovery: children are way more mature and independent than we used to think:

My social media feed is a patchwork of posts by my favorite bloggers from Kazakhstan and Moldova, news on the Lviv Book Forum, my Belorussian friend's holiday photos, ads from a tiny St.Petersburg workshop.

…

For the first time in many centuries, children will be born in Ukraine who will never in their entire life speak Russian, unless they decide to learn it. Moldova, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia are planning to reform their writing system and abandon the Cyrillic alphabet. Belarus sees protests against the existing regime beginning. The breath of the past is dissipating, and the countries are slowly becoming more independent, both politically and culturally. And we remain, as a final memento, the heirs of the empires we never saw...

It wasn’t our choice to become them, but we did become them, and this is probably enough. One day we will change history, but now we just repeat it, for the last time.”

Anastasiia Sukhoverkhova, 10th grade, general education school № 160, Kharkiv

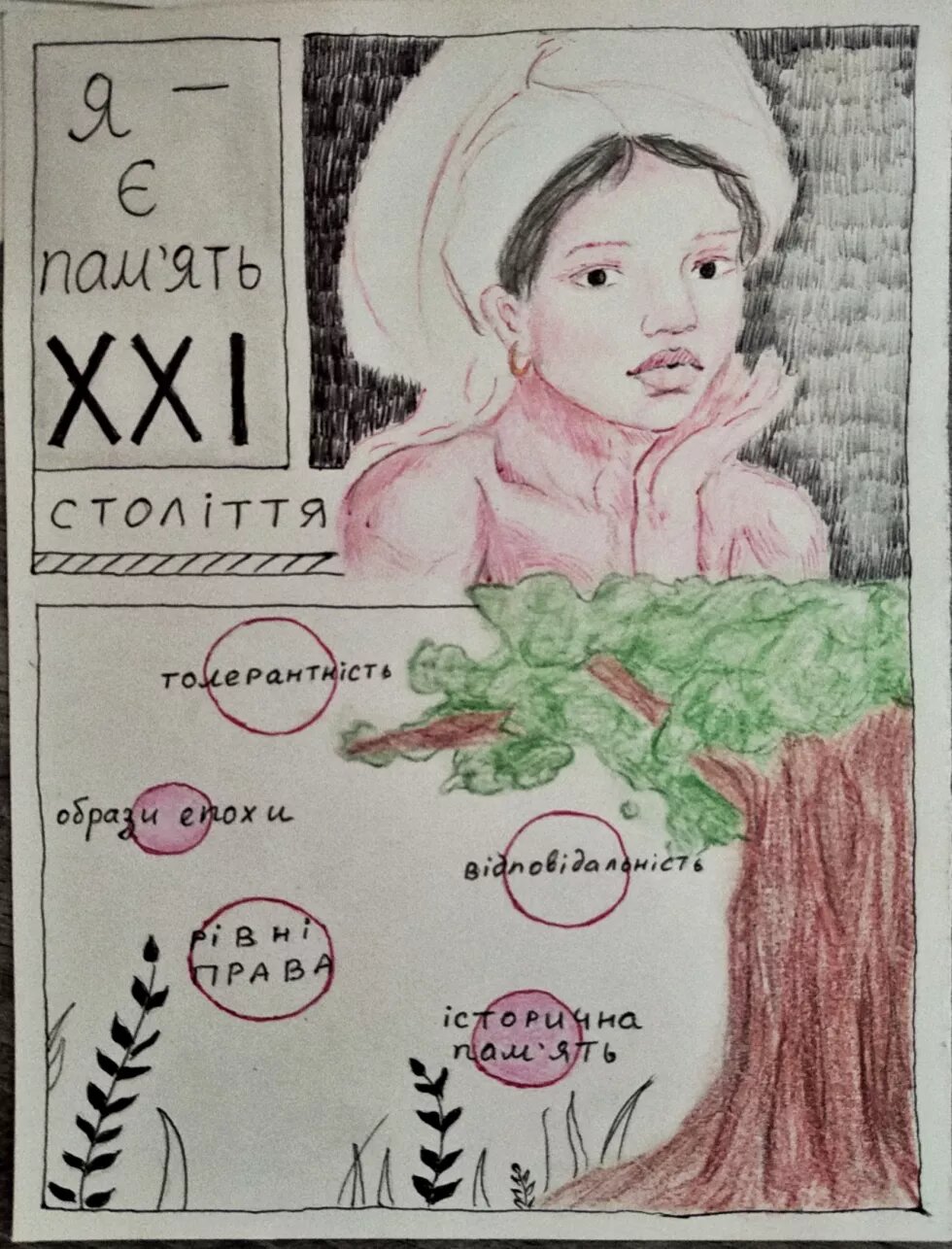

Another task for participants was a postcard, a visual illustration of an essay, or a separate story about an event of historical or even personal or family memory. Participants made drawings and collages and used graphic editors to express their joyful or often painful experience they run out of words for.

What lessons can be learned from this summer school? In what way can its experience be of use for those teachers who want to make their teaching strategies more varied?

One of the points is that one teacher is not enough for teaching history. It is worth cooperating, using interdisciplinary approaches, pushing the boundaries of sources and tasks in history classes, including informal out-of-school activities like summer schools, symposiums, research projects, interviews, etc.

If we want our society to be more just and tolerant, the public sphere to be more thoughtful, and people to be more responsible, then we must work on the tasks aimed at developing research abilities, reflection, and empathy rather than the ones aimed at absorbing and regurgitating learned material.

By Lyubov Terekhova, methodologist of the National Center “Junior Academy of Sciences of Ukraine”, PhD in Philosophy