Art historian Illia Levchenko explains how music, painting, literature and history poetized the war and secured the status of victors for the USSR.

I grew up in an independent Ukraine. And yet, every day, on May 9, my classmates and I had to go to a parade dedicated to the Victory Day of the Soviet People in the Great Patriotic War (1941–1945). These parades inevitably included a concert with the same songs. Those “victory songs” were written back during the Soviet times, but they were still sung even after the fall of the USSR throughout the entire “post-Soviet space.”

These songs are part of the myth of “great victory,” which consists of a few key assertions:

- For all Soviet people, the war was called “the Great Patriotic War,” and Soviet people here means the entire population of the USSR as of 1941.

- It was the USSR alone that saved the world from bloodthirsty fascism.

- The Soviet people were exclusively entitled to “victory,” and thus, their statements and actions were infallible.

Paintings, literature, and history also romanticized the war and portrayed the USSR and its population as winners.

These efforts strengthened the USSR’s totalitarian regime, which controlled almost all of Central and Eastern Europe.

“Denazification” of Ukraine is one of the priorities of Putin's “special operation,” which is actually a full-scale war of Russia against Ukraine. However, this idea, too, is based not on any reasonable arguments, which would attest to the escalation of far-right radical movements in Ukraine, but solely on the distortion of the memorial culture around World War II — the extension of the “great victory” myth.

In fact, “man-made” mythical ideas have underpinned the idea of the greatness of the Soviet Union and the “Soviet man,” both in Russia and in the West for a long time. When I was abroad and said that I was a Ukrainian citizen, people would “kindly” switch to Russian, without a single doubt that I must know this language and feel ecstatic to hear them say “spasibo.” Taken aback, I would try to find polite words to explain that people in Ukraine speak Ukrainian, and that interaction with the Russian language was actually traumatic for me. My interlocutors astounded me further with their knowledge of geography: “Ah, that’s Russia! We love and respect Russia!”

In the most absurd and ironic way, Putin’s Russia started exploiting the myth of victory to discredit any national policies of independent countries formed after the fall of the USSR. The only (self-proclaimed) “successor” (in the typical colonial manner) of all things Soviet was Russia. Using the victory myth for his benefit, Russia’s President Putin said, “We [Russia] would’ve won even without Ukraine.” And this line was becoming increasingly clear: while more and more Ukrainians were ready to reflect on their past (“Never again”), “Sovietness” feels like the immediate present for the majority of Russians (“Why not do it again?”).

Polls show that more and more Russians trust (dead) Stalin and support Putin’s activity — he enjoys approval ratings of up to 83%.

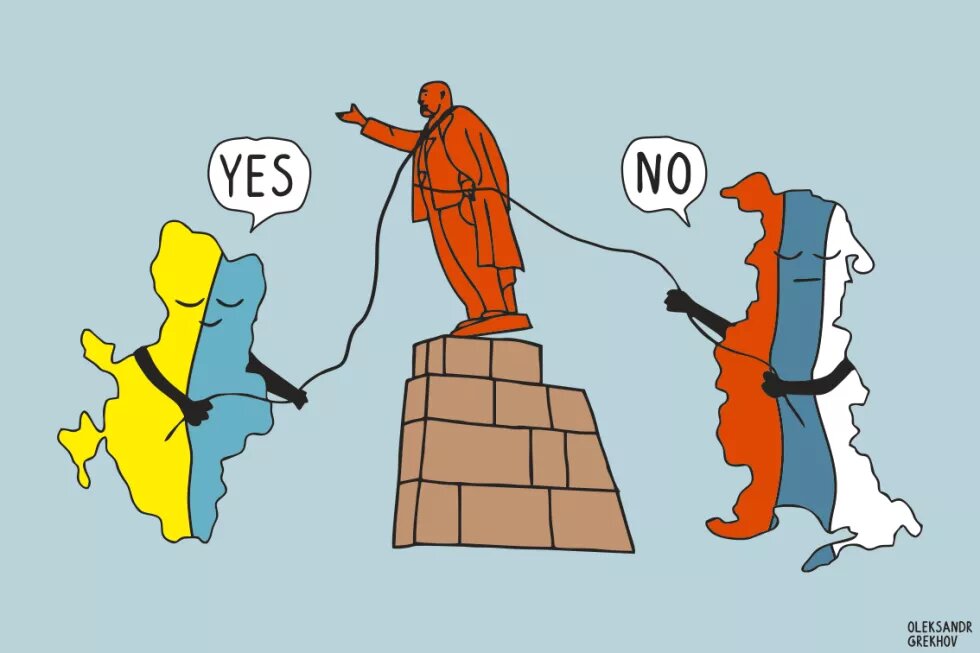

How did Russia manage to influence the former USSR republics? In all countries that obtained political- but not psychological- freedom, the USSR remained in street names, propagandist Soviet monuments, and graves of unknown soldiers, even in places where no soldiers actually died. The “unknown soldiers” had no right to name or nationality. They represented the boundless body of the homeland, for which they paid with their lives.

Russia immediately perceived any attempt by other countries to relocate monuments or tombs of unknown soldiers to cemeteries as a slap in the face, Russophobia, and a denial of the heroism of the Russian people — somehow, not Soviet anymore. Russian officials accused governments of countries where such relocation or at least artistic reinterpretation of monuments was suggested, of nationalism and fascism. Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, Ukraine, and others all encountered this response. The gap between existing Russian territories and the ones occupied by Russia is explained in a very archaic way: they talk about protecting the rights of “Russian speakers.” This is evidenced by the draft law recently introduced in the Russian State Duma, which suggests recognizing everyone who speaks Russian, belongs to one of the peoples “historically residing on the territory of Russia,” as well as people “whose direct ancestors were born, or lived, on the territory of the Russian Federation” as Russian compatriots.

Every single citizen of the USSR was completely powerless before the authority of the collective and the state. It did not even occur to such a citizen to leave, given the total power of the collective. Beyond this space, people feel responsible for their actions and employ critical thinking to process their choices and circumstances. In contrast, where the collective regime operates, responsibility is either not even mentioned, or it is conveniently shifted onto one single person.

The potential elimination of this person is thus a form of self-preservation and self-reproduction for the totalitarian regime, which continued to exist even after Stalin’s death, and even after de-Stalinization.

In recent weeks, the helplessness of the Soviet man has sounded very familiar in the posts of modern Russian bloggers with millions of followers. They childishly shrug it off. “We are little people; we cannot do anything;” “Art and culture are beyond politics.” Both statements can be interpreted to mean, “we don’t want to think about ethical choices,” or “we are not used to responsibility and would rather avoid it altogether.”

However, Russian citizens have had plenty of time to reflect on things. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine started not a month ago, but back in 2013, as a response to the events of Euromaidan, where Ukrainians expressed that they wanted European integration. Even then, it was repeatedly mentioned that Ukraine was trying to fully break from its Soviet past. During the Revolution of Dignity 2013-2014, local artists dismantled some works of monumental art. They mainly destroyed the sculptural portraits of Bolshevik leaders, scattered across all Ukrainian towns and villages, which have become symbolic of the attempts to destroy Ukrainians through famines, the Executed Renaissance, and the Great Terror. In 2015, the Ukrainian parliament passed a law deemed the communist regime and its symbols as totalitarian and equated them with the Nazis.

However, the Soviet past itself was not ready to leave Ukraine. Putin's Russia has now embarked on a favorite story about the rise of Nazism, put on a mask of the messianic people, and moved with tanks and “grads” to “enforce peace.” Even for the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Russians used a line from one of the victory songs, which should only highlight the indignity of the enemy: “On June 22, at 4 o’clock sharp, Kyiv was bombed, and it was announced that the war started.” In the official Soviet narrative, the "fascist enemy" insidiously, without an official declaration of war and seemingly without reason, attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941.

On February 24, 2022, without any announcement or reasonable grounds, Russia insidiously bombed not only Kyiv, but also about forty other Ukrainian cities, whose residents woke up from the sounds of explosions. Today, it is obvious that the attack had been meticulously prepared for many years. Perhaps this is an uncontrolled reaction of the totalitarian regime itself to disintegration processes within its dead body.

Another point is just as obvious: formal legal circumstances often only manifest intentions, but they do not reflect reality. The myth of the bloodless and peaceful disintegration of the Soviet Union was shattered by the actions of the Russian Federation. For the last thirty years, this country has not only portrayed itself as the only successor to the USSR, but also sought to restore it. Ukrainians’ refusal to consider them brothers, a sisterly republic, or “one people” undermines Russia’s status and its very foundation. The inability to distinguish people’s faces and languages within one language group is a typical colonial heritage of the unification policy, which is always based on bloodshed.

In March, billboards were spotted in occupied Crimea, with Stalin’s portrait and his quotes, saying “Our cause is right, we will defeat the enemy. Victory will be ours,” and designed to justify modern aggression of a nation that was once victorious. Neither these figures nor similar lines are yet perceived as a historicized past. As in every myth, they function beyond any real temporality: in today’s Ukraine, Russia is fighting against the collective Western enemy — “for Russia” and, somehow, “for the president.” At a recent state-organized concert, following Putin’s speech, singer Oleg Gazmanov sang a song with the line, “Ukraine and Crimea, Belarus and Moldova, that’s my country! Sakhalin and Kamchatka, the Ural Mountains, that’s my country! Krasnodar Krai, Siberia and the Volga Region, Kazakhstan and the Caucasus, and the Baltics as well…” This is actually the voice of the empire, sanctioned by the president of Russia. And this is actual recognition that all of the countries listed are ideologically in the same position as Ukraine today. Lithuanians or Poles may wake up from the bombing tomorrow at exactly 4 o’clock, as the whole of Ukraine woke up in 2022 and Georgia in 2008.

The empire still bans people from having a name, a home, or a private history. Graves of unnamed soldiers remain instead – nameless, because Russia does not pick up the dead bodies of its own soldiers in Ukraine. Instead of a home, we have cities and regions ruined by Russian bombs, millions of refugees, and forced deportation. Instead of private history, we have only the united, official, high-flown, and uncompromising history of “my country.”

Interestingly, the empire has no history. Everything it calls history is actually happening in the present. In July 2021, Putin wrote an article about the history of Ukraine. Russia is putting that “history” into practice now, using all its available weapons, having fired over 1100 missiles in over a month, mainly at civilian buildings. Ukrainians are fighting for the opportunity to speak for themselves, to write history, and most importantly, to have this history, thus leaving behind the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. To a certain extent, we are fighting to give the nameless soldier back his name, nationality, home, and history.

Translated by Natalia Slipenko