Memorial culture researcher Anna Yatsenko explains how the Soviet regime tried to assimilate Ukrainians through deportations, and the Russian government is now doing the same.

Since the beginning of Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, more than 1.2 mln Ukrainian citizens (as of May 18) have been forcibly deported to Russia from temporarily occupied areas in Ukraine, including more than 200,000 children. Incidents such as inspections at numerous checkpoints, detention at filtration points, interrogations, and reviews of documents and phones are some of the abusive experiences shared by those who managed to get out of Russia and relocate to safe countries. And what is the fate of those who remained, or did not have documents, money, or acquaintances to help them? They are being sent to remote, depressed regions of Russia. In some cases, people are even receiving postcards inviting them to settle in the Russian Far East. Indeed, by the end of April, more than 300 Mariupol residents had been transported to the Primorsky Krai. Children were immediately assigned to kindergartens and schools, though local officials complain that they have “difficulties with the Russian language.”

Russian authorities call this process an evacuation. But how voluntary is it? At least some Mariupol residents have spoken about coercion. The Ukrainian authorities insist on a different word-- “deportation”-- which constitutes a violation of international law. Directors of memorial museums of occupation in Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia compare Russia’s current actions to the mass Soviet deportations of the mid-20th century. Historian Detlef Brandes defines deportation as forced migration within a state or sphere of its influence including the territories occupied by it, to which it forces its own or foreign citizens. This distinguishes deportation from exile, which is the relocation of people beyond the borders of the state. Deportation, in contrast, may have different goals and motives. It is often used as a violent method to neutralize real or perceived opponents of an autocratic regime. This is especially true in areas where the regime's influence has been insufficient — near the border, in occupied or annexed areas.

In the Soviet Union, deportations became particularly widespread due to the need to develop its lands with harsh climates and labour shortages.

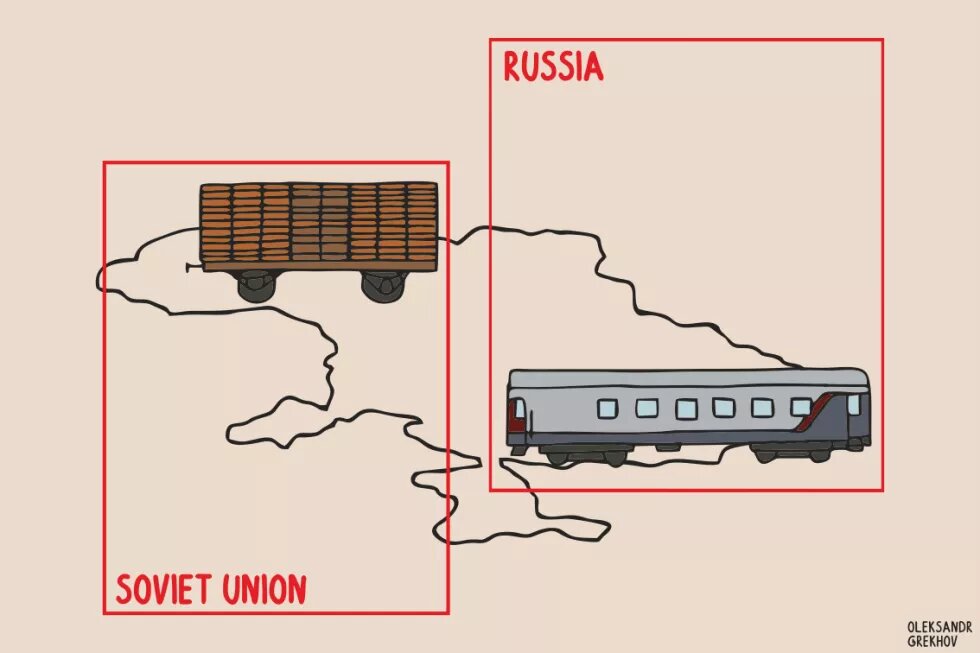

Forced relocation sought to eliminate and re-educate those whom the authorities considered disloyal and unreliable, or it was a form of punishment. Of course, Soviet mass deportations and Russia's so-called evacuation cannot be equated; however, their implementation has a similar goal — to develop depressed regions at the cost of Ukrainian citizens, and assimilate and dissolve them into the Russian population. This serves to confirm the imperial myth that there are no Ukrainians, just “bad Russians.” “As we see in the ruins of Ukrainian cities, and in the Russian practice of mass killing, rape, and deportation, the claim that a nation does not exist is the rhetorical preparation for destroying it,” believes historian Timothy Snyder.

Soviet mass deportations began in 1918 and lasted for more than 30 years. They affected over 6 million people representing various ethnic, social, and religious groups.

The first deportations from Ukraine took place in the 1930s. At that time, wealthy peasants ("kulaks"), as well as ethnic Poles and Germans from the border regions, were deported to Kazakhstan because they were considered potential spies. With the outbreak of World War II, deportations accelerated. In 1941, Germans were evicted from the south and east of Ukraine on suspicion of sympathizing with and expecting German troops. In 1944, Crimean Tatars, along with Armenians, Bulgarians, and Greeks in Crimea, were deported, and they were held collectively responsible for collaborating with the Nazis.

The regime paid special attention to Western Ukraine. Between 1940 and 1941, about 200,000 ethnic Poles, Jews, and Ukrainians were deported to Siberia, Central Asia, and the Russian Far East. By 1953, 210,000 additional people had fallen victim to forced movement. Most of them were family members of the Ukrainian nationalist underground who were considered illegal, were serving time in the GULAG camps, or had died. Also among them were families of wealthy peasants who resisted collectivization, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Anders army soldiers. The liberation process began a year after Stalin's death and lasted until the mid-1960s. Only in independent Ukraine, however, was it truly possible to restore all civil rights and give people an opportunity to speak freely about what they had endured.

The subject of deportation, as well as other crimes of the Soviet period, is marginalized and silenced in modern Russian political memory.

In September 2021, in the article, "On the New Cities of Siberia," Russian Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu described the state’s plans for developing the region. In particular, he said that the idea of grandiose construction was not new, because "in Soviet times, Siberia welcomed hundreds of thousands of young people who came enthusiastically from all over the country" and who "stayed here to work, coming from the western regions of Belarus, Ukraine, the Caucasus, Volga region and Central Asia.”

Roman Skytsky is now 75 years old. He recalls entering the University of Lviv: “There was a so-called first department. And once every six months, a KGB officer sat there, and it was like a game. He knew who I was and who my father was. And he’d always say, ‘Why did your parents move so far away from Lviv?’ Well, the standard response was, ‘They were very enthusiastic about the Soviet authorities and wanted to go build communism.’ And I was obviously saying nonsense. But that’s what you were supposed to do.” In reality, Roman's father was deported to the GULAG camps, and he and his mother, as well as his grandparents, were deported to the Russian Far East. One in six people deported from western Ukraine would end up there. Both for the Soviet authorities and for the modern Russian state, the easternmost regions remain the primary destination for the forced resettlement of Ukrainians.

Parents, spouses, children, parents-in-law, siblings, aunts, and uncles — if you were considered an enemy by the regime, your entire family became a potential enemy. Historian Tamara Vronska calls this practice “holding families hostage.”

Lists of those subject to deportation were formed in secret. Soviet authorities would break into one’s flat at night or at dawn. They would give people a couple of hours to get their belongings-- barely enough time to pack essentials. Everything else would be confiscated. Most people were deported immediately, but from the end of 1948, they were taken first to transfer points, where they could be detained for months. From there, they were transported in freight cars, which were disguised with the words "wheat," "volunteers," or “cattle." The road to the final destination was long and exhausting. Due to the lack of medical care, and the cold and hunger, not everyone survived the journey.

The newcomers had their ID documents taken away, which were replaced with special certificates. From that point, they became “special settlers.” It was forbidden to leave the settlement, and from 1950, people were forced to sign a "voluntary consent" to exile for a lifetime. They could face up to 20 years in prison for escaping. People were assigned to an enterprise, mainly in mining or forestry. Work was mandatory. Evasion was punishable by eight years in prison. Those who were physically weaker than others were sent to collective farms. Those who could not work at all were considered dependents. They were paid even less than local workers. Roman Skytsky's mother, Iryna, wrote in a letter to his father in the camp: “I am only terribly sad that I cannot help you. Because just think, I worked hard on the road, I thought I would earn at least 10 rubles a day, but it turned out to be 2.50 a day, and I worked there for 8 days basically for free. I cannot even buy myself a coat and pants.”

One of the goals of Soviet deportation was linguistic and cultural assimilation. This was especially true for children. They had access to only a Russian-language education, so they had to adjust. Although Ukrainian was spoken in the family, people were forced to switch to Russian on the doorstep. Ideological education required children to participate in communist organizations for youth. Marta Vvedenska, who was 12 years old at the time of her deportation, recalls being locked up with her classmates at a school in the Tomsk region and forced to join a “pioneer” group until her parents caused a scandal and took away their children.

Education, however, was a privilege, not the norm. Due to lack of clothing, shoes, and textbooks, and to illness and malnutrition, one in three children did not attend school. Many children had to work side-by-side with adults on logging, coal mining, the building of factories, and road construction. Those who were able to complete their studies could not obtain higher education due to mobility restrictions. Even after their formal dismissal, certain majors in higher education remained inaccessible to them.

Women accounted for almost half of the total number of deportees. The survival of the family depended mainly on them: caring for children and parents, and taking care of food, clothing, and housing.

This was all done while also engaging in hard, overtime labour. In addition, they were threatened with sexual harassment by enterprise management, settlement administrations, and local men. For example, Iryna Skytska was harassed by the head of the local post office. For a long time, she did not receive letters from her husband from the camp. It turned out that her letters were not reaching her because all of them were being intercepted by the chief postman. He assured Iryna that her husband was no longer alive and offered to marry her. Historian Tamara Vronska says that, indeed, the authorities encouraged the creation of new families. They were promised a plot of land and a loan to buy building materials, hoping that people would stay there forever. Often such relationships were not about romance. On the contrary, marriage became a survival strategy.

Dissolving people into the proverbial “cauldron” of other nations is yet another means of assimilation. Other, forcibly deported populations from western Ukraine included Germans, Poles, Lithuanians, Estonians, Latvians, Crimean Tatars, and others, alongside the local population. Due to the negative image of "Bandera bandits" created by Soviet propaganda, the deportees were met with fear. Over time, relations improved, but Ukrainians still held together. For example, they tried to marry among their own, often to people from the same region or even the same village.

Preservation of cultural identity not only supported the “special settlers” in terms of morale, but also became a unifying force, a kind of resistance. They got together in secret to celebrate religious holidays and wear traditional attire. They created choral and theatrical groups and musical ensembles. Their works, however, could not go beyond amateur art as they were subjected to verification and censorship. Anything that aroused the slightest suspicion could lead to accusations of "anti-Soviet propaganda" and imprisonment in camps. Roman Zheplynskyi and his brother organized a bandura band in Siberia. In an informal conversation, the secretary of the party organization warned him that "rumours were circulating" about the preparation of bandura players for the Shevchenko holiday, although the poet’s works were either banned or still considered “nationalist.” The party official asked not to divulge that conversation but gave “friendly advice” not to perform such songs officially in the club. Otherwise, the band members risked being sent to various “remote places.” Nadiya Lohoza ended up as one such deportee, sent to the Amur region. There, she sang Ukrainian songs and recited poems with other young people. She was arrested after somebody reported her and was sent to a GULAG camp for five years.

Today’s full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war poses entirely new challenges. However, historical parallels help us understand the basis for Russia’s current violent practices. The experience of Soviet mass deportations has been rethought in different ways: for Ukraine, it is a tragic past, and for Russia, it conjures nostalgia for the possibility of again developing remote areas of its empire. Most victims of the Soviet mass deportations from western Ukraine returned home as soon as the opportunity arose. This was possible due to quiet resistance against the policy of assimilation. Why is this experience important today? Because it reminds us that, although the methods of violence are unchanged, we know the ways to resist.

The text uses excerpts from oral history interviews with people who survived the Soviet mass deportations recorded by the team of After Silence NGO in 2021–2022; as well as materials from Tamara Vronska's unpublished monograph "The Uncertain Contin[g]ent: Deportations from Western Ukraine in 1944–1953, Everyday Life, Return.”

Translation: Natalia Slipenko