Historian of American history Oleksandra Kotliar and art historian Illia Levchenko explain how the Soviet Union planned to seize Finland 80 years ago by the same methods as Russia uses in the war against Ukraine today.

On YouTube, it’s fairly easy to find the song Receive Us, Beautiful Suomi (“Принимай нас, Суоми-красавица”). It accompanied Soviet soldiers (including Ukrainians) when attacking Finland from November 1939 to March 1940. User comments under the video suggest endless adoration and glorification of the Soviet soldiers and triumphant statements in Russian about victory in the unannounced war, which the USSR called a “defence” war, which was “necessary.”

“We had to,” “we had no choice,” “we were provoked” —these statements date back 80 years during the Winter War, whose ultimate goal was to seize the territory of Finland and incorporate it (or, in the aggressor language, “recover” it) into the USSR.

Receive Us, Beautiful Suomi has an entirely new connotation in Vladimir Putin’s newly altered phrasing. “Whether you like it or not, put up with it, my beautiful,” said Putin in his address to Volodymyr Zelenskyy before the beginning of the full-scale invasion. This is not simply a metaphor, but a very transparent idea: to enter the body of the “beauty” (the country overall and women on the occupied territories, in particular), thus asserting Russia’s dominance.

To justify the war against Finland, the Soviet Union used a tactic we now know all too well: forming a globally unrecognized quasi-state entity on the territory near the border.

The same scheme was used by the USSR in Transcarpathia (1945), and then by Russia in Abkhazia (2008), Ossetia (2008), Crimea (2014), and Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts (2014). In 1939, the Finnish Democratic Republic (FDR) became such a quasi-state, proclaimed on December 1, 1939, led by the communist Otto Kuusinen. The fake republic allowed the Soviet leadership to portray the conflict as internal: in response to a request from the League of Nations, Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov rejected accusations of war and justified the country's actions citing a treaty of mutual assistance and friendship with the FDR of December 2, 1939. In fact, power in the FDR did not go beyond the bayonets of the Red Army.

If there is no declaration of war, there is essentially no war.

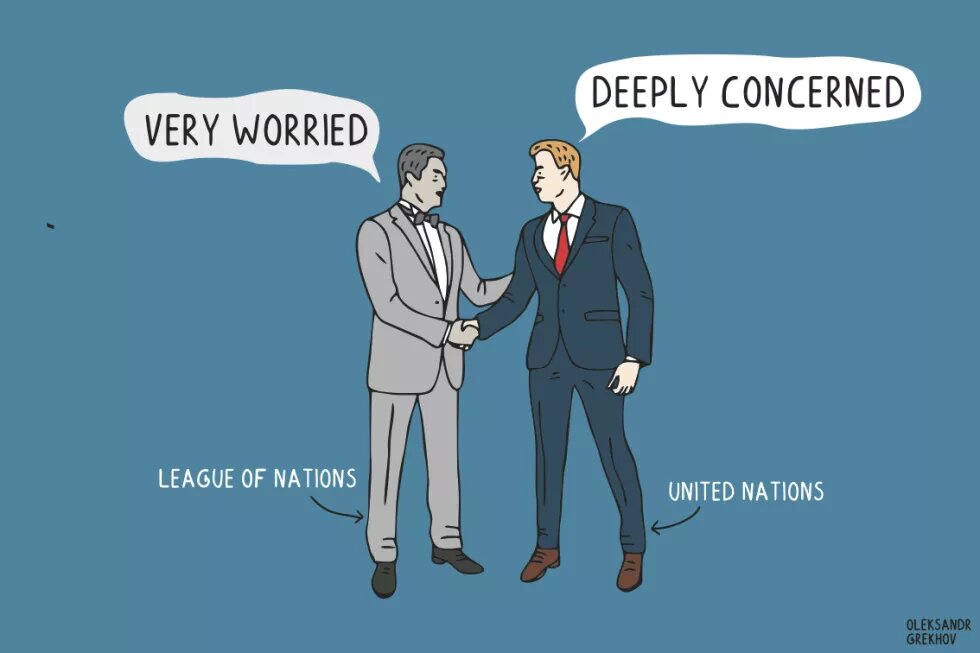

There is no bombing of cities, civilian casualties, or soldiers killed in action, whose deaths were carefully concealed in the Soviet Union. If there is no war, there can be no punishment in the form of trade and financial sanctions or severing of diplomatic relations as provided by Article 16 of the Covenant of the League of Nations, aiming to maintain peace worldwide. The League of Nations was created by European leaders after World War I. After World War II, it was replaced by the United Nations (UN). Today, neither the League of Nations in 1939, nor its successor, the UN, has been able to identify "evil" in time and to prevent its actions.

In Soviet school textbooks, the Soviet-Finnish war was conveniently called "strengthening the security of the northwestern borders of the USSR." The Soviet Union gained the opportunity to "strengthen" its territory by conquering neighbouring states as a result of the Nazi-Soviet pact signed on August 23, 1939. The agreement also contained a secret protocol on the division of spheres of influence in Europe between Germany and the USSR. The Soviet Union included Finland in the sphere of expansion, conveniently "forgetting" that it had undertaken to guarantee the sovereignty of this state under the treaties of 1920 and 1934. It should be noted that, during the first stage of World War II, Hitler and Stalin acted hand-in-hand: they implemented the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, dividing up Poland, while the German Wehrmacht and the Soviet Red Army held joint parades. These events somehow escaped becoming part of the official history of the USSR and Russia, since, for Russia, World War II was instead the Great Patriotic War, which started only in 1941 when Germany attacked the USSR.

It is also notable that the Soviet Union joined the League of Nations at France’s initiative in 1934, right after the Famine of 1932–1933 in Ukraine. The artificially imposed famine was not a substantial enough reason for the international community to respond. The USSR welcomed this lack of action. Political purges of the intelligentsia, clergy, and other "politically harmful elements" throughout the Soviet Union’s republics followed suit. The Great Terror of 1934–1937, the Executed Renaissance in Ukraine, and the “black night” in Belarus did not raise any eyebrows, apparently. It was at this time that the USSR, after a long period of isolation, became a full member of the world community. The absence of condemnation and sanctions as stipulated in international agreements effectively legitimized the crimes of the Soviet government.

In early December 1939, shortly after the invasion and the criminal crossing of the Finnish border by Soviet troops, Finland's representative in the League of Nations, Rudolf Holsti, called on the organization to intervene in the conflict to resolve it. Each member of the League of Nations had this right in accordance with Article 11 of the Covenant, considering peace was the whole reason why the organization was established. The then-Prime Minister of Finland, Risto Ryti, formulated a single demand for the USSR to “leave in peace” an independent and free nation: “We Finns have this lofty and sacred cause; we fight for our independence and our existence; we fight for our homes, our families, our children, for the right of future generations to live… But for what are the Russian workers and peasants fighting?”

More than once in the League of Nations, the Finnish government appealed to the Paris Pact of 1928, which declared its renunciation of war as a policy instrument, and to the 1933 London Convention on the Definition of Aggression, which considered its various manifestations, including undeclared war. Both international documents were signed by the Soviet Union. That is why Risto Ryti accused the aggressor of “savage destruction of towns, the murder of women and children, the use of poison gas and by other similar means. which the whole civilised world abhors.” Despite Rudolf Holsti's fair remark about the international community's inability to protect Finland from bullets and bombs despite verbal support and concern, Europe was already in the new realities of World War II, although it did not recognize or understand it at the time. The idea of the League of Nations, according to Holsti, remained, but it did not work within a completely destroyed security system.

Due to the predictable ineffectiveness of calls for a peaceful settlement of the conflict, on December 14, 1939, the USSR was expelled from the League of Nations. However, the decision was not unanimous. In particular, the Scandinavian countries abstained during the vote. As a result, Finland was assisted by several countries unilaterally by providing a volunteer corps, weapons, and moral support to the Finns in their struggle. Support was organized mostly secretly: Norway, which had refused to condemn Soviet aggression openly, gathered 2,000 volunteers to join the Finnish army. However, due to this secrecy, only 750 people were eventually transported to Finland — this was reported by the relatives of the participants in the memoirs stored in the National Archives of the country.

US diplomatic correspondence in January 1940 testified to the limited efforts of European countries to provide military assistance to Finland. The international situation created certain difficulties for full-scale support: Scandinavian countries were concerned about a possible attack by the USSR, which was Germany’s ally at the time. Moreover, Europe firmly believed that there was no hope that this union would break down. Fearing they could become the next victims of Russian aggression, Sweden and Norway opposed the passage of British and French troops through their territories to help the Finnish. The Third Reich, on the other hand, was playing a cunning game, supporting Finland in the fight with its future adversary and simultaneously trying to find common ground with Britain and France.

The inability of the great powers, to which they delegated the organization and defence of the European security system to counter Soviet aggression, prompted Finland to work more closely with Germany.

This circumstance protected the USSR from any further liability. However, after the end of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War, the sources of Soviet aggression became apparent: it was the existential nature of Soviet expansionism. And modern Russia is not even trying to hide it, instead threatening the world with nuclear weapons.

The official reason why the USSR was expelled from the League of Nations in 1939 was the fact that it set itself apart from all the standards of international law, which most states recognized to be superior to any political ambitions. Although Russia, in its various forms, was part of the international system, it consistently failed its obligation to abide by the rules and norms of international law. The 1933 London Convention focused on the problem of justifying the war by an evasive notion of “justice.” In this Convention, the signatory countries denied the legitimacy of justifying aggression by political, military or economic means. It was to this Convention that Finland appealed in the League of Nations after the Soviet invasion. Today, the Russian Federation, which actually emerged in 1991, again speaks about its “historical rights” for lands that were once part of it. This puts it beyond the limits of international law and even common sense.

Ironically, the rhetoric on both sides was completely identical — of the USSR and the League of Nations in 1939, and of Russia and the UN in 2022. It is not just “similar,” it is seriously identical in terms of language, key narratives, and the way of interacting, particularly the acceptance of pure evil and the readiness to negotiate and compromise. But this paradox was absolutely expected. On February 24, 2022, Vladimir Putin said, “We already know how Europe will react, so we will carry out the tasks of the ‘special operation.’”

Translation: Natalia Slipenko