Usually, colonialism in literature is discussed through the lens of narratives and values contained in literary works, including normalization of superiority towards certain ethnic groups, outright racism, sexism, and aggression towards vulnerable groups, reverence for the imperial system, justification of elite cruelty, etc. All of these narratives appeared in books during the heyday of empires, and the same continue to be reproduced and multiplied in contemporary post-imperial literature.

However, focusing exclusively on narratives makes the struggle to decolonize literature too generalized. It limits the discussion to the author, their publishing house (as a hypothetical “propagandist of imperial values” that replicates copies of chauvinistic works), and bookstores that sell these books. But what about other participants in the book publishing process, including literary agents and publishing houses as business organizations whose activities are aimed at sustainable development and profit?

Languages and post colonies

In May 2022, Kadija Sesay, the founder of AfriPoetree and a representative of Peepal Tree Press, which publishes works by Black British and Caribbean writers, , once again tried to draw the international community’s attention to the problem of buying the rights to the works of these authors: “In times of decolonization, we have to really think about what decolonizing the publishing industry means. Are we investing enough in it? It’s not always about financial gain; it’s about equal access to literature.” For authors from former British colonies, selling the rights to publish their books in English to a powerful publishing house usually means that the same publisher will buy the global rights, meaning that the books will be published in English but never in African languages or other less common ones. According to Sandra Tamele, the founder of the Mozambican publishing house Editora Trinta Zero Nove, writers from her country find themselves in a similar situation as soon as they sell the rights to publish their books to a publishing house from Portugal or Brazil (Mozambique was a Portuguese colony until 1975). This is not surprising for the Ukrainian book community as well, which has been trying to distance itself from a similar Russian influence for decades.

For the past 23 years, until the beginning of Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine and the illegal annexation of the Crimea in 2014, the situation in Ukraine from the point of view of the international book business was the following: When it came to publishing books by Western authors in Ukraine, it was more convenient and profitable for the rights holder (publishing house, author, or literary agent) to negotiate with a large literary agency that could work with several countries at the same time. That meant that the required scale was most easily provided by Russian literary agencies since they usually had offices in New York/London and Moscow and covered the biggest countries of the former Soviet Union. This was no surprise to anyone: Pharmaceutical giants opened offices for the single region of Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova because it allowed them to print millions of drug instructions in Russian. IT corporations often included the Baltic states in this region, because it was convenient to manage Baltic representative offices from Moscow. Owners of FMCG brands (consumer goods) produced their carbonated drinks and household chemicals with a brief description of the product in 10-12 Eastern European languages at once. These regions were, of course, managed from Russian offices. So how would the sale of book publishing rights be any different?

For a sales manager from a Western publishing house or an agent representing a Western author, cooperation between these agencies and Russian headquarters was extremely profitable and convenient: one deal could cover almost a quarter of Eurasia. At the same time, Western agents were not eager to sell the rights to each language and each country of the post-Soviet space separately because this would mean identifying a partner in each country on their own. When an agency with a Moscow office began to exclusively handle the publication of books in the entire region, and there were no obstacles to the export of Russian-language books from the Russian Federation to other post-Soviet countries, the situation usually resulted in the book being published only in Russian and then exported to Ukraine and other countries.

If a Ukrainian publisher managed to conclude its own agreement with a Moscow-based agency for the right to publish a book in Ukrainian in Ukraine, because of the significant difference in the number of copies printed, the imported book translated into Russian was significantly cheaper for the end consumer than its Ukrainian counterpart. Synergies and economies of scale played into the hands of Russian publishers as they not only printed numerous editions, making each unit cheaper, but also had significantly larger budgets for marketing, promotion, and bookstore incentives. Some publishers later opened their own representative offices in Ukraine, while others worked through local intermediaries.

Positive discrimination for the Ukrainian book market

In 2017, almost three years after Russia’s invasion of the Crimea in 2014, Ukraine passed a law partially restricting the import of Russian books into Ukraine. Prior to that, in December 2016, it was only about restricting access to anti-Ukrainian books that promoted the greatness of the Soviet Union, glorified the actions of Soviet security officials, justified the occupation of Ukraine, incited ethnic, racial, and religious hatred, etc. For the general public and the Ukrainian book community, the 2017 law was also useful for its informational value as it highlighted the bookstores, publishing houses, and intermediary companies that tried importing anti-Ukrainian books but were banned from doing so.

In 2014, the first sanctions were levied against Russian citizens who financially supported Russia’s armed aggression against Ukraine, causing a major shift in the international book publishing community’s attitude toward the Ukrainian book market. The significant role of publishing houses, literary agencies, and authors from Ukraine who created the groundwork for this shift is worth noting. They began to actively use the achievements of the digital era to contact their colleagues directly, and they later became regular visitors to international book fairs and festivals. For example, in 2019, at the opening ceremony of the Frankfurt Book Fair, the organizers praised the path that the Ukrainian national stand had taken over the first five years of its operation, moving from a symbolic representation of the state in 2014 to a full-fledged workspace with several zones in 2019. In 2019, Ukraine also presented its national stand for the first time at the London and Bologna Book Fairs.

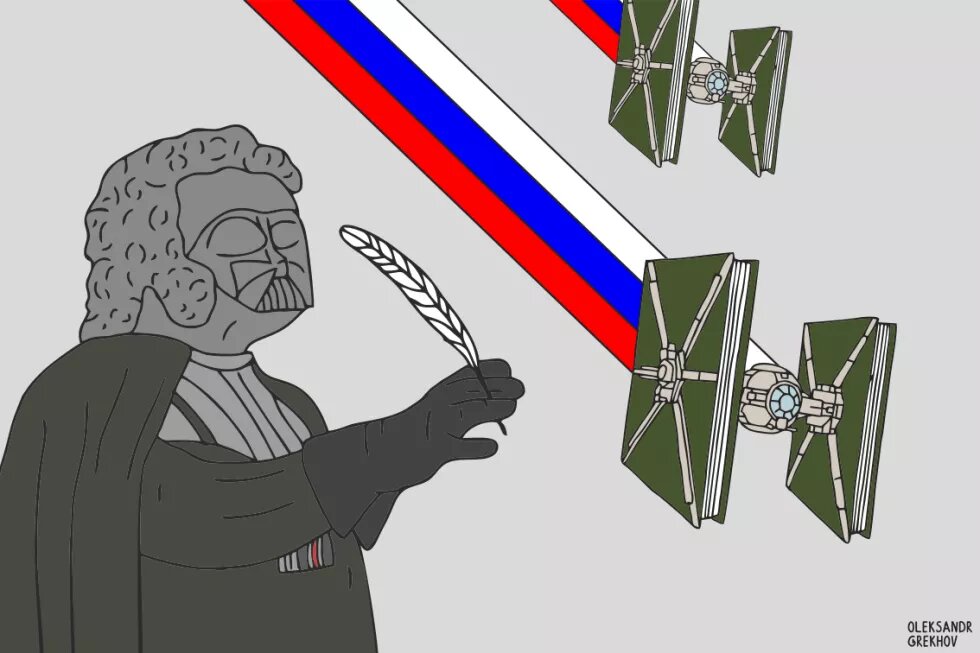

The empire strikes back

For six years (2014–2022), Russian businesses abroad learned to adapt to the new conditions and disguise their Russian origins and Moscow residences behind the complimentary avenues of New York and the high streets of London. There was no longer any question of publicly representing the interests of Western authors and publishers in the post-Soviet territories: many agencies removed references to Ukraine, Moldova, or Georgia from their websites, leaving only Russia.. However, their founders and heads now hold respected positions in prestigious international literary agencies or in the rights departments of publishing giants. And no one would accuse them of being biased or pro-Russian.

Since mid-2022, the struggle for a complete ban on book imports from the Russian Federation and Belarus has intensified in Ukraine. Unfortunately, this long-overdue initiative is unlikely to affect the functioning of literary agencies with Russian roots.

For example, the Van Lear Agency works with many well-known authors, large publishing houses, and international agencies to sell rights to Russia, Ukraine, and Georgia. Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, this agency indicated that it had offices in the United States and Moscow, and publicly articulated that it was active in the Ukrainian book market. This was stated by Alex Stevens of United Agents, one of the largest agencies in the world, and on the websites of the Madeleine Milburn Agency and Peters Fraser+Dunlop. Van Lear Agency had (and probably still has) exclusive contracts to represent famous authors. But despite its power, it and other similar agencies are not omnipotent and it is quite possible to bypass cooperation with them. This is what Ukrainian publishers who care about whom to buy rights from have begun to do.

The inability of some publishers to resist the temptation to take the easier route by concluding a deal through a Russian intermediary, even a well-disguised one, is yet another reminder of the consequences of imperialism--the unwillingness or inability of a former colony to defend its right to independence and existence. Ukrainian publishing houses should be the first to fight for the independence of the Ukrainian book market, even if it contradicts their purely financial interests.

New hope

Since February 24, 2022, many world-renowned authors have stood up to defend democratic values and the right of the Ukrainian people to sovereignty. They have been publicly condemning Russia’s armed aggression, ceasing cooperation with Russian publishing houses, actively participating in events in support of Ukraine, attending online meetings with Ukrainian audiences, agreeing to sell the rights to Ukrainian translations of their books for a nominal fee, and helping families who have been forced to leave Ukraine. PEN International’s open letter condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine alone has more than 1,000 known signatories from around the world, including Nobel laureates Orhan Pamuk and Olga Tokarczuk, as well as Margaret Atwood, Jonathan Franzen, Colm Toibin, Elif Şafak, and others. The American historian and writer Timothy Snyder visited Ukraine, as did the French writer and philosopher Bernard-Henri Levy. The publishers of these writers praised their initiative. But they had an additional motivation.. In many countries around the world, the demand for books about Ukraine, Ukrainian-Russian relations, and books of all genres written by Ukrainian authors has increased rapidly. This allowed Ukrainian publishing houses, which already had translations into English, German, and other languages, to respond quickly to the demand of their foreign colleagues. For example, the book “A Ukrainian Christmas” by Yaroslav Hrytsak and Nadiika Herbish was published in the UK and Estonia (with more countries soon to be added). Several new translations of Andrey Kurkov’s books appeared, including his diaries of the Russian invasion, as well as numerous translations of Serhiy Zhadan’s books. (The novel Boarding School alone will be translated into 26 languages.) Oksana Zabuzhko, Oleksandr Mykhed, Iryna Tsilyk, Artem Chapeye, Artem Chekh, and many others regularly publish their essays and book excerpts in the world’s leading media.

Establishing contacts and promoting cooperation between Ukrainian authors, publishers, and foreign publishing houses partially fills the gap in the field of literary agencies that would represent the interests of Ukrainian books in the international arena. Since the beginning of the full-scale invasion, almost two dozen Ukrainian publishers have sold the rights to translate their books abroad, significantly expanding the geographic presence of Ukrainian books on the world map.

Many experienced international publishers and agents realize that the demand for books about and from Ukraine will remain steadily high for years, if not decades. Unfortunately, the reason for this interest is Russia’s war against Ukraine. In its turn, the Ukrainian book community is actively working to ensure that Ukraine’s voice, previously drowned out by Russian imperialism, is heard on the international stage, and that as many book lovers as possible from all over the world learn about Ukrainian culture, language, and literature.