Language is the primary means of transmitting information from one person to another. It is so natural and universal that without language, we cannot even describe what language is. But its universal nature and our tendency to rely on it unconditionally also mean that language can be manipulated. Using linguistic means alone, you can distort reality, particularly for people who have no personal experience of certain events and therefore have to rely on how events are reported.

Russia has deliberately and skillfully instrumentalized language in the war against Ukraine.

Blood of Words

Language is a social phenomenon. We need it to share experiences and thoughts with others, and the unspoken tacit goal of every act of communication is understanding. Thus, when we encounter new words or notions, we tend to imagine they pertain to something real. When we hear a message, our primary assumption is that its purpose is to report something, rather than distract or deceive. People need to understand what exactly has been said before making a qualitative assessment of it.

Due to this phenomenon, a word or a phase repeated multiple times becomes legitimized. Language takes on only what speakers of this language bring into it; therefore, words with sufficient visibility will stay in circulation on their own, even if the concept or phrase has no meaning. This is precisely how the idea of “fraternal peoples” or “fraternal nations” functions today. The phrase does not entail any explanation of what this “fraternity” actually means. It always serves as a self-explanatory justification of Russia’s “historic right” to Ukraine. Since 2014, Russia has been justifying its war against Ukraine with the idea that the Ukrainian people are “fraternal” to Russians.

We know what the meaning of a “brother” is – a blood relative. This meaning will affect our intuitive understanding of what “fraternal peoples” are. The phrase indicates a close degree of kinship between two peoples, nothing else. But if we look at the contexts of how it is used, we have to admit that the idea of fraternity appears to be the basis for an armed invasion and genocide. Even when we consider Russia’s aggression unacceptable, even when we try to deny the idea of “brotherhood” embodied in the war, the temptation remains to further legitimize this term, bringing back its “true,” neutral meaning. We tend to believe that everything is okay with words themselves and that they mean real things: it is Russia, or even Putin himself, that distorted their meaning. Instead of considering the possible fatal error of the notion itself, we start looking for those responsible for such incorrect word usage.

Hence, for example, numerous comparisons of Russia and Ukraine with Cain and Abel. Although they express an absolutely correct anti-violent sentiment, exposing the hypocrisy of the Russian argument, they reinforce the association between Russia and a neutral form of the statement — the very idea of fraternity between Ukraine and Russia, “peaceful coexistence,” unburdened by the war and genocide. Even though the very idea of “fraternal peoples” comes from Russia and originates from about the same time as Russia’s genocidal policies regarding Ukraine.

The neutral interpretation paints the same picture as the utopian Russian propaganda of “a brotherhood of nations.” By exposing Russian hypocrisy in the use of political phrasings to justify war crimes (i.e., “unfraternal” behavior towards a “fraternal” people), we run the risk of further cementing the use of the very phrases and ideas that underlie this genocide with our own rhetoric.

Some of the first words we ever master are required to differentiate between “us” and “them,” between what is “ours” and what is “foreign.” A family member vs. a person we meet for the first time, one’s own thing vs. a thing belonging to someone else. Something to which we are entitled vs. something for which we have no claim.

Russian imperialism is based on the proposition of broad engagement. This is clearly evident from Russia positioning itself as open to the world (and the way it uses people like Gérard Depardieu or Steven Seagal to construct this cosmopolitan image). The proposed social contract is simple: you can become “Russian” if you want. In this context, Russia itself often cites the example of the USA as a “a country of migrants” to call for seamless integration into the collective Russian identity.

The problem starts when a person chooses something other than integration. Rejecting assimilation, the statement “I do not belong to this community,” albeit neutral in its essence, is perceived as negative in this discourse. Russia insists on its right to consider anyone it wants to be a natural part of Russia, regardless of political reality, international agreements, or actual identity.

Wind and Words

The issue of using on Ukraine as opposed to in Ukraine [in Russian] — similar to using the Ukraine rather than simply Ukraine in English — may seem absurd on the surface. In the first case, Ukraine is defined as Russia’s object, a province constituting a part of general geography. In Ukraine is based on the dichotomy of ours/foreign and defines Ukraine as a separate space beyond the space that is Russian. As the argument goes, these are just words. The most common explanations are quite predictable: the word use developed historically (which is not true; in the early 20th century, both prepositions were used in both Russian and Ukrainian); and these are only the rules of the Russian language, it is just how the Russian language is. Ukraine’s subordination to Russia is a fact so fundamental, you could add, that language reflects and cannot help but reflect this. Here, language but mirrors the reality: we treat Ukraine as our province and call it our province because that is precisely the way we perceive it.

It should be noted that Russian imperialism is very different from the kind to which Western communities are used. Russia expanded along its borders and did not pursue colonies overseas (except for Alaska), and its colonial policies were not about segregating “higher” and “lower” people, but rather the idea of “Russianization,” a concept alien to European colonialism (except, perhaps, for the French one, in certain aspects). The idea was that the bearers of other identities began to consider themselves Russian and thus, losing their own identity, merged into Russian society.

This makes it difficult to associate Russian with Hitleresque national-socialism. On his now-deleted Facebook page, journalist Oleksandr Mykhelson speculated that German fascism focused on genetics, while modern ruscism destroys people through their way of thinking. His point was that while German Nazis or their followers, current white supremacists, use the approach “I consider you different and, therefore, I want to destroy you,” Russia essentially says, “You consider yourselves different, separate from us, and, therefore, you have to be destroyed.” Russian imperialism is spread through the illusion of inclusiveness: anyone can become a Russian, and if you do not choose to become a Russian voluntarily, maybe you will do it out of fear for your life.

Identifying its place in the world, today’s Russia still operates with the “us vs. them” opposition inherited from World War II. After The Sinews of Peace, also known as “the Iron Curtain Speech,” this narrative shifted from the Nazis towards the collective West, then towards NATO. It survived throughout the Cold War and then, following the collapse of the USSR, remained part of Russian politics.

Victory in World War II meant that the USSR (which officially entered the war on September 17, 1939, on the side of Germany) apparently took it upon itself to “appoint Nazis.” The USSR itself, of course, could not be recognized as an ally of the Reich (1939-1941), and this historical point is concealed in modern Russia, as well. Since the USSR and Russia, as its successor, are the states that defeated the Nazis, since Nazis are the mythical archenemy of Russia, then everyone with whom Russia chooses to fight must be Nazis. Formal characteristics are not important, but only the vocabulary of Russian politicians. If Russia is at war with anyone, it is at war with Nazis because war with Nazis is what Russia does. This is basically the logic used.

Fixing Names

Russia is never at war with countries. A war with a specific country is something too official, and the very fact recognizes and legitimizes the existence of said country and its government. Therefore, it is an “internationalist duty” (Afghanistan), a “war against terrorists” (Ichkeria), a “special military operation” (Ukraine). And they fight, respectively, with “gangs of Mujahideen,” “Chechen terrorists,” and “Kyiv-Bandera junta.”

In general, the very first level of Russian aggression is normally to deny its target’s agency, which of course, includes the general “inability” of a certain country to be sovereign. It also includes stories about the political terrorism of the “hand of the West,” and the results are positioned as the victim’s inherent defect. But the very first stage is to deny the victim their own name. This is not only things like the derogatory khokhol for Ukrainians or churka for people from Central Asia. Even when the opposite side is an entire country, it is reduced to a single leader who “betrayed” Russia or “incited” people to revolt. A country has no sovereign will. An individual has no personal will. The country does not exist, and an individual does not really mind becoming part of Russia. The problem is allegedly always in a single person from the “enemy” side, antipathy or hostility towards Russia is always “instigated” by a specific person, who “prevents” ordinary people from self-fulfillment as Russians. Russia, a state that has never existed without vozhdism (eng. ‘leaderism’), uses this idea above all to discredit democracies.

However, this tradition dates back many centuries. Ukrainians who tried to gain autonomy or independence after Russian occupation after the Battle of Poltava were Mazepins. Ukrainians who fought for independence in the first half of the 20th century became “Petliurites.” Ukrainians who have been fighting for their state since World War II until today are called Banderivites. These concepts ignore ideology, the struggle for independence, and generally any political context. They appoint one single person who is allegedly responsible for a conflict with Russia, and everyone else simply “followed them.”

The myth of the Banderivites fits perfectly well into the general Russian narrative of “victory over Nazis.” Russia is not concerned about the spectrum of political views among Ukrainian insurgents themselves (and not all of them were even nationalists), and it will only be happy if no one outside of Russia is interested in it, either. Since Ukrainian rebels fought Russia during World War II (while also fighting Germany), Ukrainian rebels are Nazis. Because, remember, Nazis are what Russia fights against. Since Stepan Bandera was an iconic and rather controversial political figure (although he had nothing to do with the rebel army), all Ukrainians who fought against Russia from World War II onwards are automatically Banderivites. This artificial linguistic construct is then further embellished with decorations that speak to the European public’s prior experience. There is often no room for debate or argument because the message itself is simple enough and repeated often enough that it feels unquestionable. No new term has been coined to replace Banderivites during the Russia-Ukraine war, which I believe may be attributed to two reasons. First, Europe continued to live in the post-Nazi narrative, and there was no point in coming up with a replacement for an idea already connoted with universal evil. Secondly, the large amount of information in real time prevented the effective creation of a counter-narrative in which Ukraine is an aggressor or a criminal. Failing to create the “fair war” facade, Russia continued to use a term associated with a part of history that is much lesser known to the general public.

Nazi Germany and Hirohito’s Japan also used language with a similar goal. Post-war investigations proved especially difficult because of the bureaucratic, “inside” language that masked crimes. “The final solution of the Jewish issue” instead of physical destruction. “Logs in Squad 731” rather than test subjects in a death camp. “Harvest and grain shortages” rather than genocide through artificial famine.

Language as a Tool

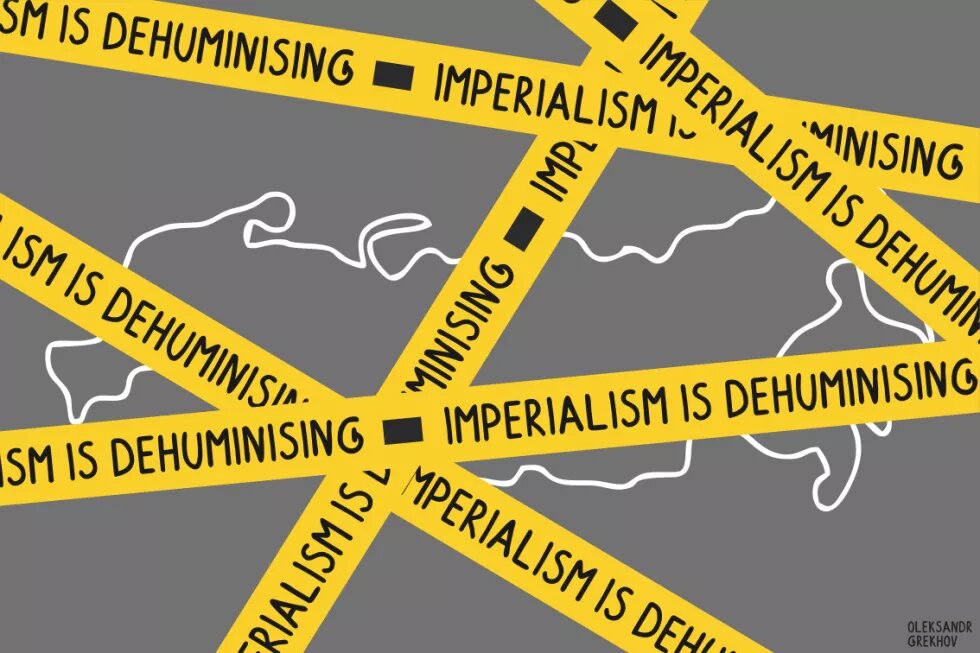

Russian vocabulary is dehumanizing. We are all human and we are all sometimes prejudiced. We understand very well that lexical dehumanization is the first step towards alienation, creating the “radical other” who does not generate empathy because soon they will be reduced to a linguistic cliché, rather than a human being, a people, or a country. It is easier to destroy someone who is not considered human. We saw how this happens in Bucha, Irpin, Borodianka, Izium, Mariupol, Kherson, and hundreds of other Ukrainian cities and villages.

However, from Russia’s perspective, it was not Russians killing Ukrainians. It was “fighters against Nazism eliminating Banderivites and criminals,” or simply “khokhols and little Russians.” Language matters because it explains our world to us. The Russian world is a language of ambiguities. It is a language in which certain words take on a certain meaning for the foreign public, which should avoid “interfering in the internal affairs of another country” (which is what Russians use to call genocide as they carried it out). And these same words take on an entirely different meaning, particularly emotional, for the internal user, for people who were born and raised in a system that cultivated hatred of every neighbor and a willingness to kill a neighbor on command. Until the war is over, until the guilty are punished, and most importantly, until Russian imperialism, which gives rise to this language, is broken entirely — until then, Russian-language discourse cannot be neutral. Modern Russian language is a party to this conflict.

Natalia Slipenko, translator