How have pacifist values in Europe changed during Russia's full-scale war against Ukraine? Do countries that are not at war need weapons, and can they protect democracy? These are just a few of the hundreds of questions that arise within the circles of so-called green movements and initiatives in Europe. In peaceful circumstances, they stand up for what they refer to as green values: environmental sustainability, gender equality, and participatory democracy. Pacifism is the foundation of that worldview. But what does this mean, and how is this ideology changing in the context of the war in the middle of Europe?

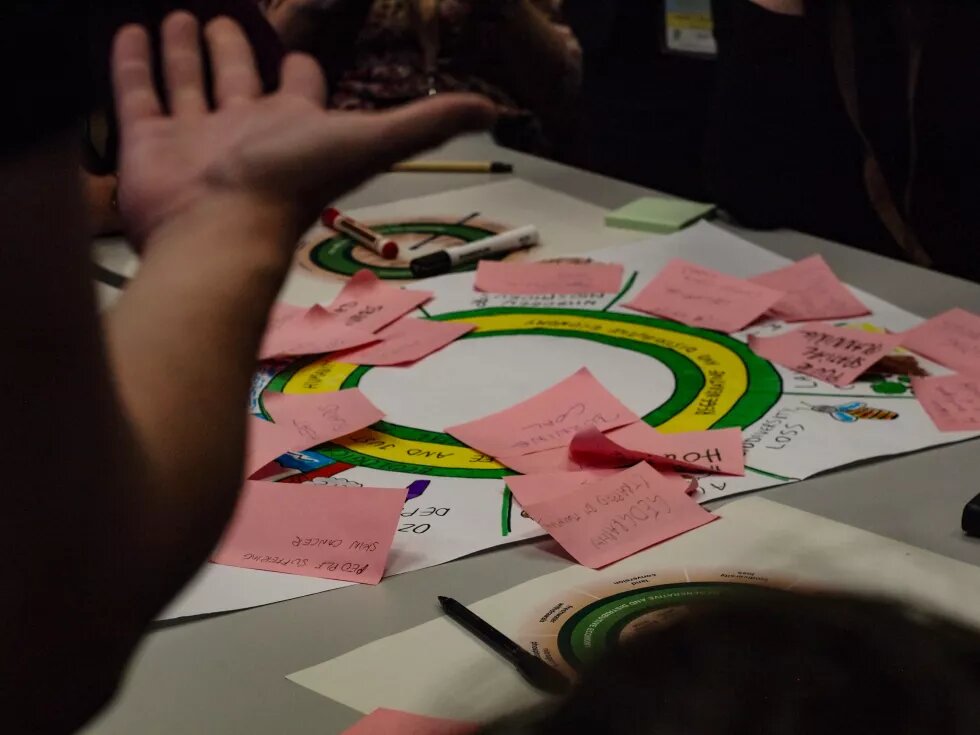

In mid-November 2023, Warsaw hosted the European Green Academy, a multi-day event that brought together representatives from green movements in the EU, specifically activists and politicians. The Ukrainian delegation consisting of graduates from the Ukrainian Green Academy also took part in this event (which you can read about by following the link).

This text provides answers to some of the key questions currently arising in discussions about European semi-democratic systems. In particular, it addresses issues related to war, self-defense, and the role of democracy in the context of weaponry.

How do pacifist values change in times of war?

Pacifism, by definition, is the ideology that condemns any war and rejects it as an instrument of foreign policy. Therefore, pacifism does not justify war under any circumstances.

“Absolute pacifism is not so much about peace being good and war being bad. Instead, it is the belief that a person should never engage in war, even in self-defense. However, the right to self-defense is enshrined even in Article 51 of the UN Charter, and there are reasons for this,” explains Christina Kesler, a member of the Executive Committee of the Federation of Young European Greens.

Countries that have not experienced war can often discuss pacifism in the abstract. Christina adds that it is quite easy to take a position of absolute pacifism from this perspective.

“Things become much more complicated when faced with the specific conditions of war or when making a political choice that involves war, such as decisions regarding military assistance,” she adds.

According to Kesler, many green parties and their representatives are now distancing themselves from the ideas of absolute pacifism, while simultaneously advocating for peace and viewing war as a terrible phenomenon.

“But they also recognize that there isn't always a perfect solution. Sometimes, you need to choose in favor of an imperfect solution — the lesser evil.”

Neutrality to the aggressor means support for the aggressor, explains Olha Nykorak, Coordinator of the Human Security Program, Heinrich Boell Foundation in Ukraine.

“Peace is not the default constant. And it is impossible to treat the aggressor and the defending state equally because the initial conditions of these countries are unequal,” she adds. The concept of war is constantly changing, especially now, explains the coordinator, “the concept of neutrality was defined by The Hague Convention No. 5 back in 1907. The war was entirely different back then — between more or less equal subjects, the main reason being the redistribution of resources, and the method involving meaningless bloodshed. But the Convention is still in force, and the concept of neutrality has not been reconsidered.

“But the full-scale war in Ukraine is an existential struggle for the right to be oneself, for democracy, and for belonging to Europe. Demonstrating the ability to protect oneself is helpful even in seemingly hopeless situations. If you want peace, prepare for war; this has been known since ancient times,” adds Olha Nykorak.

Why do democratic countries that are not engaged in wars need to maintain an army?

“Unfortunately, rational arguments and appeals to democratic values and the rule of law do not work with aggressor states. Here, the analogy with a school bully is more appropriate; calls to morality are much less effective than confidence in a retaliatory strike,” notes Olha.

If we continue this analogy, it is not always necessary to resort to force — often, the mere presence of a powerful army, allies, and effective weapons serves as a sufficient deterrent.

“Seemingly weakened by internal political processes and a prolonged hybrid war, Ukraine, without nuclear weapons, appeared as an easy target. However, it is extremely difficult to form a combat-ready army that would give a worthy rebuff to the aggressor in war conditions. The future is completely unpredictable, so states that enjoy the luxury of a temporary peace actually gain time to prepare,” adds the coordinator.

“You can't unilaterally abandon a system where some states use troops and weapons to achieve their own goals,” emphasizes Christina.

“Therefore, for a country that is not engaged in war, the army is akin to health insurance. You hope that you will never need it. But if the worst-case scenario does come true, then you are ready — you have the means to protect yourself and resist. No one likes to think about the possibility of becoming seriously ill and requiring expensive treatment. And no one likes to contemplate the possibility of an invasion. The probability of both events occurring may seem minimal. But the consequences are so devastating — to the extent that you can't simply ignore the risk,” the expert explains.

Despite this, Western societies are often too slow to modernize their idea of militarized security, despite the militarization of processes around them.

“If we talk, say, about the Green Movement, it has not formed its holistic vision of foreign policy. While being effective in climate diplomacy, the transnational dissemination of democratic values, and feminist foreign policy, the Greens have not reached a consensus on defense and security issues. Especially in the face of aggression. Discussions are becoming more active, particularly in the context of the European Parliament elections in 2024. The popularity of extreme populist parties in Europe is growing, manipulating general anxiety. Therefore, the development of policies should be deliberate and adapted for each state, while simultaneously being based on common values,” explains Olha Nykorak.

Is it possible to build or preserve democracy with weapons?

Olha Nykorak believes that the arsenal of democracy against authoritarian regimes is weaker.

In the case of such a contrast, it should be understood that, for example, the pluralism of opinions opposes a population mobilized by propaganda, and limited power opposes sole power.

“Therefore, the concept of defense-capable democracy (not militant democracy, as it is often incorrectly translated) is appropriate here. War also poses a greater threat to the environment, both directly through fighting, mining, etc., and less obviously because valuable renewable energy resources, such as lithium, end up in the hands of an uncontrolled autocracy. Green values are not about toothlessness and naivety; they are about what we defend, what we stand for, and what we can lose,” says the Coordinator of the Human Security Program.

Christina Kesler notes that weapons do not interfere with the preservation or construction of democracy, but it is important that they be subject to democratic control.

“This includes, for example, the belief that members of the armed forces are committed to democratic values. Wherever there are cases of right-wing extremist groups in the armed forces, these instances should be treated completely transparently. It also means that democracies need an open discussion with citizens about the tasks of the armed forces — what they should be and what they should not be,” she says.

And democracy itself will be preserved through free and fair elections, civil liberties like freedom of the press, and the involvement of civil society, Kesler believes.

What role do platforms like the European Green Academy play in such discussions?

Events where European and Ukrainian activists, politicians, and other representatives of civil society meet to discuss topics related to Russia's war against Ukraine are primarily a tool for dialogue and the protection of common values.

“Such events primarily provide an opportunity to hear each other — in a safe and tolerant environment. Try to put yourself in the other person's shoes, move your thoughts and emotions to another corner of Europe — both the one that is currently not in danger and the one where war has become commonplace and inevitable. Explain personally why yesterday's ardent Ukrainian pacifists are now learning to use weapons and taking tactical medicine courses. The distance and Ukraine slipping out of the information space have an impact — it is essential to regularly explain the realities of a thousand kilometers away to colleagues with common values. And together make democracy able to defend itself,” says Olha Nykorak.

In addition, it is thanks to the discussion of difficult topics, such as militarization, that platforms like the Green Academy become a place for constructive discussion.

“The reality is that security remains a complex issue for Green parties across Europe. But difficult topics don't go away if we ignore them,” adds Kesler.

An important aspect is also that it is Ukrainians who are invited to discuss the European green movements.

“On platforms such as the European Green Academy, various players developing green initiatives in the EU are increasingly interested in and discussing militarization, military budgets, and support for Ukraine. I like the unanimity of this support. And I am delighted that the Ukrainian delegation is invited, ensuring that the conversation about us does not take place without us — although this is usually a platform for green initiatives within the EU. We add this connection with reality to the discussions and guide others to plan their activities in accordance with the reality around them,” explains Olena Anhelova, Coordinator of the Ukrainian Green Academy.