COVID-19 uniquely affects women. Here are many of the ways it does.

I. Introduction – COVID-19 Is Aggravating Existing Systemic Inequities

Everything in our social world is gendered, and so it is no surprise that the COVID-19 pandemic with its demands for shutdown of economic activities and mandated push for social distancing is not gender-neutral either. The gender dimensions of the pandemic are numerous and numbingly severe, but they are not new and not surprising. In fact, if anything, the invisible coronavirus has made visible the many already existing fault lines in our hyper-globalized and largely corporate-driven world with its economic, environmental and social injustices, persistent gender inequality and sexism, violent xenophobia and racism, neocolonialist oppression and extractivism perpetuated by financial, political and intellectual self-proclaimed elites.

The pandemic hits the world at a time when the international community meant to focus on taking stock of achievements over the past 25 years in implementing the Beijing Platform of Action with its global commitments towards comprehensive gender equality and the fulfillment of women’s universal human rights. The fundamental reorientation of our societies, cultures, and systems that it advocates for is today more important than ever. Many feminists, gender advocates and women’s organizations on the eve of this important anniversary already felt that they were running just to stay in place and stem the tide of widespread sexism and resurgent misogyny. And then the COVID-19 pandemic hit. While it has made their work in envisioning a comprehensive cultural and systemic change even more essential, not the least because even today, too few women can add their voice to decision-making at multiple levels that will structure more immediate emergency responses and the outlines for a long-term recovery and the global systems of the future, many feminist and women’s rights organizations are under an existential threat as resources for their continued work, now needed more than ever, are diverted.

The COVID-19 pandemic is not the root cause, but a reinforcement, exaggerator and aggravator of that what has been discriminatory and unjust before in our systems and communities, including by oppressing, utilizing and victimizing women and girls in many areas of daily life. Viruses don’t discriminate, societies and systems do. It is no coincidence that the dominant economic pattern and thinking has consistently exploited existing gender stereotypes and belittled women’s and girls’ contributions in sustaining societies, such as by making care work largely invisible, underappreciated, underpaid and undervalued. The fight against the coronavirus must therefore be comprehensive and systemic. It cannot be limited to the level of virology and relegated to improving health systems, but must attack discrimination and inequality at home and abroad on multiple interrelated cultural, political, social, and economic levels by applying a feminist, human rights-based, intersectional and justice-oriented analysis throughout based on collaboration, global solidarity and reinvigorated multilateralism to counter nationalist and authoritarian retrenchment and competition.

II. Feminist Focus on and Women’s Leadership for a Post-Pandemic Systems Change

Gender advocates and many feminist groups and networks in numerous contributions as well as resource compilations collected over the past weeks have articulated core feminist principles that need to guide such a systemic paradigm shift for the post-pandemic era. They have also outlined priority actions and safeguards required to address the existing inequalities and injustices that have already exacerbated previous calamities such as wars and conflict, displacement, natural disasters, climate change, economic and financial crises, or prior health emergencies. The same, just at an even higher and universal level, is happening with the COVID-19 pandemic as the denial of people’s fundamental social, economic, cultural and political human rights continues, such as through required quarantine and distancing, for new groups of people previously unaffected.

In their contributions and analyses, gender specialists and feminists remind decision-makers and citizens worldwide that we must use the momentum – and initiatives, resources, research, actions and discourses – directed at dealing with the pandemic wisely to start transforming how our societies operate and how they protect, benefit and empower the most vulnerable and marginalized populations, and in particular women and girls. They are also mounting a collective effort to track governments and corporations’ actions and hold them accountable for initiating now the fundamental shifts needed. That means integrating gender equality and intersectional and human rights based approaches that prioritize the well being of people, their participation in decision-making and their access to essential services and resources centrally in all COVID-19 pandemic and post-pandemic research, plans and policy documents for targeted responses at local, national and global levels.

If implemented, such priority actions, to name but a few, will increase investment in public health systems; expand social protection schemes for universal coverage, including for informal and undocumented and unpaid care workers; cancel developing countries’ existing debt; guarantee access to and eliminate regulatory and legal barriers against sexual and reproductive health care services as well as fund measures to address gender-based violence and hold perpetrators accountable; safeguard democratic elections by adapting and reforming election laws and voting procedures for compliance with coronavirus public health concerns; and generate significant additional financing for those needed response measures, including by reducing and redirecting military funding as well as increasing industrialized countries’ development and humanitarian assistance as a matter of justice and global solidarity.

Utilizing the opportunity for a better post-pandemic global system also means not repeating the failures and quasi gender-blindness in dealing with previous threats and emergencies, such as Ebola or Zika, by collecting and applying gender-differentiated data as well as data on intersecting multiple discriminations such as age, race, ethnicity, or ability and by involving and financing communities and grassroots organizations, including indigenous peoples’ groups and women-led and feminist organizations, in articulating and implementing local pandemic responses. The right lessons learned and important structural changes brought on the way without compromise and excuses now will also avoid pitting the well being and rights of people against the environment and our planet. If anything, the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic has shown the interconnectedness of global health emergencies with the climate and biodiversity emergencies, including the increasing likelihood of a pandemic repeat. We cannot allow the focus on the COVID-19 pandemic to even temporarily overshadow those other looming emergencies no less pressing for the survival of humanity. Therefore all social, political and economic recovery measures for the coronavirus crisis must also push for decarbonization and incorporate a feminist vision for a global green new deal and just transition.

Lastly, in times of a cataclysmic global crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic, both failures and examples of true leadership, including in particular of political leadership, are revealed, and with it the need to re-evaluate what leadership qualities we seek in those supposed to help guide societies experiencing multiple and intersecting humanitarian, economic, social, health and political crises into a post-pandemic world that will be in many ways fundamentally unlike our pre-pandemic one.

Comparing different national responses – and leadership styles – to the coronavirus crisis, a number of gender experts and observers have pointed out that female leaders at the helm of such diverse countries as Taiwan, New Zealand and Germany, as well other female heads of state in several Nordic countries have highlighted how communicating empathy and care in times of crisis is a strength, not a liability. Their success in limiting the worst excesses of the pandemic in their countries is even more impressive, when recognizing that at the onset of the pandemic only 10 of 152 elected heads of state were women and thus just around 7% of all global political leaders. Compare this to the style of a group of male leaders around the world, perhaps most starkly in Hungary, who have used the crisis to accelerate authoritarianism, undermine the separation of powers and resort to blame-gaming instead of providing steady crisis direction. This only showcases what social scientists have confirmed before to varying extents, namely that some gender differences in leadership effectiveness exist.

In the context of the coronavirus pandemic and other systemic crises some of the beneficial traits associated with female leadership such as knowing one’s own limitations, motivating through transformation, putting people over self-aggrandizement, humility, focusing on elevating others and empathizing instead of commanding could help in promoting more gender-responsive, equitable and human-rights centered responses. At the very least, the diversity of approaches and experiences in addressing and thinking together public health and human security should be an argument for a more equal representation of women at all levels of decision-making. It could, for example, influence how parliaments (currently 75% male worldwide) safeguard and protect human rights and how gender-responsive the measures they approve are and whose implementation they should oversee in the wake of COVID-19 and thus how we build a better future.

In the following sections, this paper will explore in more detail the gender-differentiated impacts of and responses to the coronavirus pandemic needed, drawing on a growing body of relevant articles, analysis and advocacy recommendations in response to the multiple and deep-seated systemic challenges brought to global attention by the pandemic before ending with a short outlook. In particular, it will analyze in more detail:

- The gendered economic impacts in both crisis and recovery, particularly gendered employment patterns, reconsideration of what is essential work, gendered patterns of informal work, the role of women migrant and undocumented workers, the gendered dimension of global supply chains, and the focus and cover of the first slew of national economic recovery measures;

- A new recognition and appreciation of care work, such as paid health and social care, unpaid care work, school closures and the impacts of education, as well as who makes healthcare decision globally;

- Gendered coronavirus health implications, looking beyond the COVID-19 infection itself to analyze pandemic-related limitations to women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights and the health concerns and sexual rights of LBGTI and gender non-confirming people; and

- Personal and communal safety and security implications, particularly gender-based violence and domestic violence, human trafficking and humanitarian needs affecting refugees and internationally displaced people particularly during the pandemic.

Table of Contents

- Introduction – COVID-19 Is Aggravating Existing Systemic Inequities

- Feminist Focus on and Women’s Leadership for a Post-Pandemic Systems Change

- Gender-Differentiated Economic Impacts from COVID-19 in Both Crisis and Recovery

- Putting a Spotlight on Care Work

- Gendered Health Implications

- Gendered Safety and Security Implications

- Outlook – Overcoming the Pandemic and Building Resilience Against Future Emergencies by Investing in Human Rights, Gender Equality and Expanding Human Security

III. Gender-Differentiated Economic Impacts from COVID-19 in Both Crisis and Recovery

Globally around 2.7 billion workers or 81% of the global work force are affected by the partial or global lockdown measures due to the coronavirus and the world economy is heading into a deep global recession expected to be quite different and more severe than previous ones. Many of the gender-differentiated impacts and injustices of the dramatic economic downturn caused by the COVID-19 pandemic internationally, nationally and locally, which affect women disproportionately worse, have already become quite obvious, as do the sets of interrelated actions required for a gender-responsive, human-rights-based and just and equitable pandemic response and post-pandemic economic recovery. If these gender differences and fundamental human rights are not taken into account in national and international response or recovery plans and packages by including gender-responsive and rights-based economic and social policy measures, gains made over the past decades in labor force participation and economic empowerment for women as well as addressing and reducing the feminization of poverty will be lost. This would further compound the existing fragility of livelihoods as significantly more women than men are living in extreme poverty globally, among them a disproportionate number of female-headed households and especially single mothers.

A. Gendered Employment Patterns

In contrast to past economic recessions such as the 2008 financial crisis when more men than women lost their jobs, due to the social distancing and shutdown measures to deal with the coronavirus, the loss of employment because of the COVID-19 pandemic affects women more severely. Globally, women have disproportionately large shares of low-paying service jobs, as well as part-time and temporary jobs and dominate in informal work arrangements. Many of these jobs do not provide protection under traditional safety nets and job-related benefits such as health insurance, paid sick and maternity leave, pensions and unemployment compensation, as these frequently depend primarily on full-time formal participation in the labor force. This is more often the case in low-and middle income countries, but affects also women in high-income countries including in North America and Europe, where similar gender-differentiated employment patterns hold.

While women represent less than 40% of total employment globally, they make up 57% of those in part-time jobs. The majority of temporary workers or those with casual work arrangements are also women, many among the first to lose their jobs during the pandemic. Of those employed in the service industry, 55% are women, with a few female-dominated low-wage service sectors such as retail, food services and hospitality, tourism and accommodations accounting for 800 million workers altogether. Women in these sectors are particularly impacted by job losses and reduced work hours because of the pandemic. In low- and middle-income countries, these hard-hit sectors have a high proportion of workers in informal employment and with limited access to health services and social protection. In the retail sector alone, globally 482 million checkout clerks, shopkeepers and sales people are impacted, many working in businesses considered non-essential experiencing widespread closures and employment reductions. For example, in the United States 77% of those working in clothing and shoe stores are women, the majority of them women of color. The accommodation and food services sector, where women make up a majority of employees, is also severely affected, accounting for 144 million workers worldwide and suffering from almost full closure in some countries and a steep decline in demand where operations can continue. In the United States, for example, 70% of all wait staff are women, including a disproportionate share of women of color.

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), women’s traditional care responsibilities are a primary reason for this sex-differentiation in terms of job quality, job security and work-related social, health and retirement benefits. All over the world women with care responsibilities are more likely to be self-employed or with temporary jobs, to work in the informal economy and are therefore less likely to pay into social security systems. Mothers of children under 6 years old suffer the highest such “employment penalty.”

In many countries and for many of these jobs, gender differentiation intersects with race, education or immigration status. Those earning low wages as maids, home aids, cleaners, or store clerks are also often among the most marginalized and disadvantaged. Adding insult to injury, women still earn significantly less for the same job as men. Globally, the gender pay gap is stuck at 19%, but in some countries such as Pakistan women are paid up to 35% less for the same work as men—independent of job description or pay grade. This significantly undermines the ability of working women to absorb intersecting health, social and economic shocks such as the one delivered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few examples can illustrate this effect of gender and its intersectionality on earning and income potential further. In the United States, ‘Equal Pay Day’ was commemorated on March 31st by women’s rights activists, marking how many days extra women have to work this year to catch up to US men’s earning last year. With American working women only paid 82 cents per every dollar paid to men, this adds up to life-time earning losses of around $4 hundred thousand for white women, but more than doubles to close to $1 million for black women, Latinas and indigenous women. This gender pay gap can be observed irrespective of profession and income level, but it is worst when comparing the earnings of mothers to fathers—doubly when considering that 15 million households in the United States are headed by single mothers, many of them women of color.

B. Reconsideration of Essential Work

While many women have lost their service jobs or seen their work hours reduced due to the COVID-19 pandemic, other women continue to work in service sectors that are deemed essential such as food distribution or health care. They face a higher occupational health risk because of the pandemic. It is quite an eye opener to see which jobs are deemed to be essential during this crisis and recognize with shame that their valuable societal role is routinely underappreciated and undercompensated in our economic system with low wages and few to no social benefits. It is a public disgrace that many of our societies are now asking women in these low-paying service jobs, many of them undocumented immigrants or migrant workers, to take on risks as essential workers to keep the public fed, to care for the sick and vulnerable and to maintain clean and safe environments. In the past, the same societies and systems have denied them the dignity of a decent livelihood with a living wage and social appreciation and protection for a worthy job done well, but they should not continue to do so in the post-pandemic future.

Globally, there are 136 million workers in human health and social work activities, including nurses, doctors and other health workers, workers in residential care facilities and social workers, as well as support workers, such as laundry and cleaning staff, who face serious risk of contracting COVID-19 in the workplace. Approximately 70% of jobs in the sector worldwide are held by women. In many countries, this percentage is even higher, such as in the United States, where women make up 78% of this vital sector and African Americans are over-represented (almost 18% of the employed).

A recent British study concluded that the risk of exposure in essential jobs is very unevenly distributed between men and women. It found that of the 3.2 million jobs considered high-risk roles in the United Kingdom (working in essential positions as nurses, pharmacists, doctors, grocery clerks, or prison and police officers) 2.5 million or roughly 77% were held by women. However, the lowest-paying of those jobs were almost entirely, namely 98%, staffed by women.

C. Gendered Patterns of Informal Work

Around 2 billion people or 61% of global workers are in the informal economy such as self-employed day workers, meaning they are not or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements that provide them with social, health or job protections.They fall out of the purview of labor laws leaving many exposed to low pay, exploitation and unsafe working conditions. These poor conditions are exacerbated by labor discrimination, sexism, racism and xenophobia, which many informal workers face, with women, particularly migrant women, over-represented in the informal work force. One of the most vulnerable forms of informal employment is contributing family work. Globally, women comprise 63% of these workers, who are employed without direct pay in family businesses or farms. In developing countries 90% of the overall workers and 79% in urban areas are in the informal sector. For women in developing countries, the informal sector is the primary source of employment. In some regions of the world, such as in South Asia, up to 95% of female workers work in the informal sector or 80% in non-agricultural informal jobs; in sub-Saharan Africa and Latin-America and the Caribbean this figure is 74% and 54% respectively for non-agricultural informal jobs.

Restrictive containment measures in many developing states such as India, Nigeria, Brazil, Vietnam, Pakistan or China in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are already severely affecting tens of millions of informal workers, many of them women and migrant workers. In India alone, more than 400 million workers in the informal economy, which employs almost 90% of all workers in the country, risk being pushed into even deeper poverty. Some of the most draconian and stringent lockdown measures have lead to apocalyptic scenes of millions stranded and without options as they are forced to return to rural areas without income or livelihood alternatives.

In developing countries, many workers in the informal sector, the majority of them women, provide essential services to ensure urban food, care, and sanitation systems continue to function during the COVID-19 pandemic. Women in the informal sector in the global South work as street and market vendors, goods and service traders, waste pickers, and domestic workers in precarious economic and social conditions without legal or social protection, and now during the coronavirus crisis are at increased personal risk with little or no alternative. Often evicted and underappreciated before the pandemic hit, advocacy groups working on behalf of those in the informal sector feel that the recognition among policy-makers and the public in developing countries is growing that without the services of informal workers entire urban systems could collapse. As a result, many cities have made exceptional provisions for some informal workers during mandatory lock downs.

With many women in the informal sector working as subsistence farmers or seasonal workers in agriculture, the largest sector in most developing countries, their continued work for little or no compensation, often as contributing family workers, is essential to prevent growing risks to food insecurity due to containment measures, including border closures. As the virus could spread further into rural areas where there is an even greater lack of social support and health care systems, women and girls are likely to face the double burden of increased demand on the unpaid care work of women to compensate for the lack of formal services. Additional strain is placed on them to secure the food needs of their families, communities and countries.

D. Women Migrant and Undocumented Workers

More than 258 million migrant workers live and work in other countries, many in the informal sector or as undocumented immigrants, contributing to the economic wealth and wellbeing of both their host and home countries and supporting another 800 million family members in their origin countries through remittances. In 2018 alone, remittances reached $529 billion and represented more than three times the annual flow of official development assistance (ODA). Asia, and in particular South Asia, is the primary source of migrant workers globally.

More migrant women are in the global work force than non-migrant women, mostly concentrated in female-dominated care and service sectors in the informal economy. The estimated 8.5 million women migrant domestic workers are one of the most vulnerable migrant worker groups, as they are subject to poor working conditions, long and often unlimited working hours, frequently with insecure and exploitative contracts and limited to no social protection. Already vulnerable to abusive employment conditions in normal times, their risk of abuse is heightened during the COVID-19 pandemic, because they are often frontline caregivers without adequate protections and little power. Women migrant workers are also more likely to fall prey to unethical labor brokers, who through coercion and deceit expose them to precarious or exploitative hiring arrangements and a number of other human and labor rights violations. In the worst case, they are subject to sexual exploitation, such as in prostitution markets in the European Union mostly made up of migrant women from outside or within the EU who are in this situation either by deliberate force or lack of alternative economic choices.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many migrant workers face exclusion from many COVID-19 related health and social services in their host countries, as well as stigma and discrimination, particularly when undocumented. Many undocumented migrant workers are denied health care and are rounded up for detention and deportation, while in some countries they have been scapegoated for spreading the disease. Thousands are trapped in their destination countries, unable to return home because of closed borders, lack of money, or legal restrictions, such as the kafala system in the Gulf countries, which ties migrant workers to a single employer. Others are forced to live and work in unsafe, crowded and unsanitary conditions with imposed quarantines that increase their risk of infection. At the same time, many migrant workers, with their work in agriculture or health and social care considered essential during the pandemic , continue to pick produce, manufacture essential products or deliver essential services, but without adequate safeguards for their health and wellbeing.

The situation of migrant and undocumented workers in the United States puts a spotlight on some of the community’s gravest concerns during the coronavirus crisis, even in rich industrialized countries, with significantly more severe impacts in many developing countries. An estimated 8 million undocumented workers live in the United States, many of whom work as wait staff or cooks, cleaners, social or health care providers, or farm workers, in some of the industries hardest hit by the pandemic and sectors where their work contributions are considered essential during the crisis. More than half have no health insurance, despite having lived in the Unites States for more than a decade. Even in times of the pandemic, they live with the fear of running into immigration enforcement. The US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which has not put a moratorium on operations during the coronavirus crisis, has only committed to refraining from picking up undocumented immigrants near or at medical facilities. An estimated 2 to 3 million migrant farm workers, roughly 900,000 of them women, are still expected to work during the Covid-19 pandemic. The Trump administration declared food and agricultural workers ‘essential’ workers, but left them largely unprotected and excluded from the most basic labor protections, despite their exposure to severe occupational risks, including pesticides with an acute impact on farm workers’ health and lives, especially for women. While in the United States a $2.1 billion stimulus bill has been approved, it explicitly excludes undocumented workers and their families, for example from receiving unemployment benefits. Even documented immigrants working in the United States could be penalized for using public benefits if they try to apply for a green card later on; this could have a chilling effect on many immigrant workers applying for benefits they are entitled to such as food stamps or state and local aid services.

Global migration networks and migrant worker advocates are thus stressing that in order to safeguard migrant workers’ lives, public officials must take the lead in respecting non-discrimination and ensuring equal treatment for all regardless of migration or documentation status. They urge governments and employers to uphold the rights of migrant and undocumented workers. They demand making the regularization of migrants and migrant workers an integral part of the response to the crisis by focusing on inclusive, rights-based and gender-responsive approaches. Measures to relieve the social and economic consequences of the crisis should fully include migrants and refugees without discrimination, including those working in the informal economy, and with full inclusion of migrant women workers in domestic and care work. These measures can include wage support, insurance, and social protection; measures to prevent bankruptcies and job loss; crisis-related worker and unemployment benefits; extensions on the payment of taxes, rents, mortgages and other financial obligations; and the renewal of migrant worker contracts and visas. A number of countries have taken some initial steps. For example, Portugal has temporarily allowed some undocumented people to access public services and social security benefits on the same level as citizens; but many others need to follow suit and such measures need to be extended indefinitely.

E. Women Workers in Global Supply Chains

The COVID-19 pandemic is disrupting global markets and trade as well as supply chains around the world. It is also showcasing how some of the existing global trade patterns have been built on the backs of the poorest workers and especially women workers, many of them migrants and in the informal sector. International trade agreements put pressure on developing countries to lower tax rates, compete with cheap labor and production costs and externalize environmental and social impacts of the global race to the bottom. These structures benefit overwhelmingly the few, such as large transnational corporations shopping for jurisdictions and well-connected and corrupt political and economic elites in developing countries, to the detriment of many and the environment. According to the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC), an astounding 94% of the employees of the world’s 50 largest transnational corporations are hidden within global supply chains. Workers’ rights advocates monitoring the impacts of the pandemic worry that potentially tens of millions of global supply chain workers could lose their jobs with minimal or no compensation. There are more than 150 million workers in low-income countries producing goods for export to the industrialized North, with tens of millions more service jobs linked to transnational corporations in wealthy countries. Around 50 million of these workers, predominantly women and often the main income earners of their families, are concentrated in sectors such as apparel, textiles and footwear. Women predominate in other global supply chain sectors as well, such as the global trade in flowers. With many flower farms concentrated in East and Southern Africa, in Kenya alone tens of thousands of flower pickers, almost all women in casual low-paid work arrangements without protections, have been sent home as demand for fresh cut flowers has dropped due to the coronavirus crisis. Few of the workers at the start of the global supply chains are paid enough to tuck away savings and many are already caught in debt traps. This highlights both the unsustainability of our supply chain system and the need for global solidarity and support.

Consider the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on garment workers, where around 90% are women, often coming from rural areas with few employment alternatives, and who now face destitution. Millions of these workers in Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and other countries have already been outright fired or temporarily furloughed without severance pay, even where it is legally mandated like in Bangladesh or Cambodia, as many Western big brand-name buyers have canceled their orders or refused to contribute to mitigate impacts on affected workers. This is despite the fact that many of these brands claim to have “responsible exit” policies. Without Western brands and retailers stepping up and doing the right thing (as some of them have done) by agreeing, at minimum, to pay for orders that factories were already in the process of producing, garment workers are left destitute and without fallback options. This is because in the vast majority of garment producing countries, there are no or only insufficient social protection mechanisms such as health insurance, unemployment insurance or guaranteed funds in case of insolvency, at least in part as a result of decades of downward pressure on the prices paid for garments. Just recently, thousands of destitute garment workers in Bangladesh, the majority women, protested in the streets to be paid for work already done.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, labor rights activists challenge manufacturers, service providers, brands and retailers to work jointly with governments in developing countries where global supply chain workers are located toward addressing these shortcomings by establishing and improving national social safety schemes. If corporate social responsibility is to be more than a buzzword, then global supply chains should be restarted based on a reformed pricing model. It should allow for the gender-equal payment of living wages as well as gender-responsive social benefits. Worker safety should be in line with government obligations. Transnational corporations’ legal accountability for protecting and respecting the human rights of all global supply chain workers should be increased in the developed countries where they export to.

F. Economic Recovery Measures

Job losses and business closures are surging globally, with livelihoods lost and poverty increasing even in the industrialized world. In the United States alone over a four week period 22 million people have filed for unemployment, with food banks unable to address growing food insecurity. However, in developing countries, particularly the poorest and most fragile, conflict-ridden and highly indebted ones, the losses of development gains and prolonged economic and social devastation are even more pronounced. Many of these developing countries have already suffered successive waves of fiscal and structural adjustments with reforms that curtailed labor rights, weakened social protection schemes and exacerbated the precariousness of many work arrangements. This makes tens of millions of people – and particularly women with their heavy concentration in the informal and service sectors – more vulnerable as the economic effects of the pandemic hits them and their countries.

While 168 countries have passed some kind of fiscal response package to address the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic amounting to more than $5 trillion and counting, in the overwhelming majority of developing countries those response packages are exceedingly small. For example, a least developed country like Zambia is only able to devote 0.01% of its (much smaller) GDP for an economic response versus 9.2% of Sweden’s (much higher) GDP. Many of the countries in the global South lack the fiscal flexibility to marshal any adequate emergency response at all.

This is why broad and comprehensive debt forgiveness, not just temporary debt relief, as well as a substantial and sustained increase in developed countries’ official development assistance (ODA) of at least $100 billion additionally to developing countries is needed as a matter of morality, justice, humanity, global solidarity, and also as a matter of gender-responsiveness. This is also in the enlightened self-interest of richer countries. In globalized systems during a pandemic converging with other humanitarian and ecological crises, nobody can be safe from the virus and prosper until everyone is safe.

With so many countries in the process of formulating their economic and social responses to the coronavirus, it is crucially important that those recovery packages include a broader gender and human rights assessment, although there is currently little evidence that many of them do so in a systematic way. Such an assessment would provide the basis for designing and implementing gender-responsive and human rights-centered policies and recovery measures that not only focus on providing some immediate support and relief, but also plan to address underlying structural gender inequities in the economic system while not contributing to or creating new ones. A primary focus must be on existing social protection systems, which the global COVID-19 pandemic has revealed to be insufficient even in developed countries, because they largely exclude many women’s economic participation in part-time, at will or informal work from coverage. Both the collection of gender-disaggregated data (complemented by other factors such as age, race or ethnicity to gain more specific knowledge of how gender intersects with other factors) as well as the specific targeting of women (and in sectors where women’s economic participation is dominant) will be necessary to address already existing shortcomings aggravated by the impacts of the coronavirus.

A focus on the gender-responsiveness and human-rights integration of economic and social policies and plans globally and nationally would also apply lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic, where in many instances gendered recovery plans and analysis were absent. For example, a seminal World Bank report on Ebola’s economic impacts failed to discuss gendered economic impacts of the epidemic. As a consequence, men’s income returned to the pre-outbreak level much faster than women’s income after the outbreak, with many women never fully recovering economically. Some good practice experience from the work of a non-governmental organization during Ebola recovery efforts in Sierra Leone also showcased that recovery outcomes were best when response measures did not choose between addressing immediate needs or structural inequities, but did both. The latter also highlights the importance of including civil society organizations, and specifically women’s organizations, directly in the delivery of response measures to address the COVID-19 pandemic and recovery.

Overall, fiscal and economic response to the pandemic must start long overdue structural reforms for redistributive justice in many countries, including progressive taxation reforms like imposing a wealth tax toward recovery proportional to rich individuals or corporations’ fortunes. States must also reduce and redirect military expenditures, with military spending planned for 2020 in more than 130 countries. The top 10 countries having budgeted a combined $1.4 trillion for defense alone. In the post-corona world, military might and defense is less important than investing in overall human safety and security by redirecting public funds toward basic service provisions and on creating sustainable long-term employment and a greener economy. During the pandemic, rather than observing artificial debt ceilings or debt limits (including as an excuse by rich countries to not support regional and international solidarity post-pandemic recovery measures), states must dramatically increase spending that targets inequalities and poverty caused by the COVID-19 crisis and tackles underlying structural inequities, the UN Independent Expert on debt and human rights warned in a letter to governments and financial institutions. He asked them to ensure that any bailout for corporations, banks or investors comes with stringent human rights and social conditions and accountability attached.

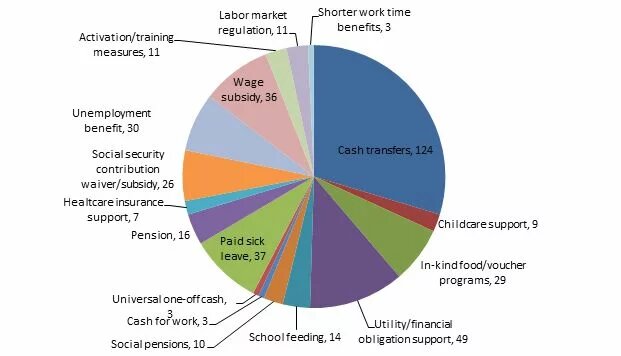

A detailed analysis of 418 separate social protection and jobs programs introduced by 106 countries by early April shows that 241 interventions focused on social assistance such as cash transfers, childcare support, food and other vouchers, school feedings or social pensions, followed by 116 programs of social insurance such as paid sick leave or unemployment benefits, and 61 programs focusing on supply-side labor market interventions such as wage subsidies, compensation payment for shorter working time or training measures. Overall social assistance measures now reach 593 million people. The largest single country contribution to the global coverage is India’s social assistance efforts attempting to include 440 million.

Social assistance interventions such as food vouchers or direct cash transfer might be one of the best immediate response measures during the pandemic to ease economic and social burdens for women and their families. These should, where possible, build on or expand existing programs and also use different delivery models, such as mobile banking to counteract the fact that fewer women have banking accounts or access to credit. However, such social assistance interventions do not address nor build future resilience to health and economic shocks in the same way that expanding social protection schemes—for example to cover all-part time, temporary and informal work predominantly done by women—would do.

In terms of social insurance, in coronavirus economic coverage packages paid sick leave is the most frequently adopted measure, including in countries like Algeria, El Salvador, Finland and Lebanon. However, the International Trade Union Federation (ITUC) found that even with such measures multiplying, free health care was still only available in half of the countries analyzed, with more money in these packages spent on bailing out businesses than providing sick leave for all workers. Unemployment benefits are also widely used, including for example in Romania, Russia, and South Africa, although it is not clear if this is largely extending the length or amount of unemployment benefits for those employees previously covered or bringing new groups of unemployed such as the self-employed, part-time employees or those working in the informal sector, where women’s work is concentrated, under the social protection scheme. To be gender-responsive, the extension of unemployment benefits has to specially target those work sectors most affected by COVID-19 crisis in which women are heavily represented or even dominant, such as teaching, social care, tourism, food and hospitality, or retail.

Labor market interventions are another key way in which governments should provide support in a gender-responsive way. To account for the reality of women workers in many countries, wage subsidies, which make up the biggest share of economic recovery measures analyzed in 168 countries, should be extended to informal workers (as for example Thailand and Peru have done), including measures that specifically cover domestic workers.

Figure 1: Distribution of 418 Social Protection and Job Programs in 106 countries by type. Sourced from World Bank/ILO Data — licence infos

Lastly, financial support targeted to businesses needs to take into account that women-led businesses are over-represented in the micro and small enterprise categories, which are the backbone of most countries’ economic recovery, but won’t profit from business bailouts targeting big business, and in many countries have difficulties accessing loans, let alone at affordable rates and with suitable conditions. Government programs in order to be gender-responsive in their business sector responses thus need to focus on providing businesses and enterprises in feminized sectors, such as social care and service provision or as small business traders, with subsidized and state-backed loans, tax deferrals and exemptions. And in order to bring recovery money and relevant information to women, they should include women’s networks, women civil society groups or microfinance and savings groups as finance recipients and as intermediaries for information and finance delivery.

IV. Putting a Spotlight on Care Work

If nothing else, the COVID-19 pandemic and its global repercussions have removed the cloak of invisibility from care work – both paid and unpaid – and put a spotlight on its importance for the survival of economies, societies and families by highlighting the disproportionate contributions made and risks taken by females. The pandemic is also laying bare the intersections of economic class, race, legal status and geography with gender in form of the economic and social under-appreciation of care work, which in its paid form is often only compensated at minimum-wage level and thus severely underpaid for services provided for the well-being of societies as a whole. It is no coincidence that our societies have routinely outsourced indispensable paid care for our children, the sick, people living with disabilities and the elderly mostly to women, and especially to those women, who themselves are socially, economically and politically marginalized and disadvantaged, such as women of color, migrant workers or people with insecure immigration status. The economic and social recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic must focus therefore on a true valuation and commensurate political and social validation of paid and unpaid care work in our social safety, health care, retirement and education systems and focus on the corresponding reforms necessary.

A. Paid Healthcare and Social Care

Partially as a result of cultural and social stereotyping and limited career opportunities and the resulting occupational -segregation, it is women who make up 70% of the more than 136 million workers in the health and social care sectors globally according to the World Health Organization (WHO), while earning on average 11% less than men for doing the same job. While in all regions of the world there are more male physicians than female ones, among nurses, midwives and community health workers the ratio of female workers to male ones is turned upside down by wide margins. This also illustrates the existing workplace gender biases, discrimination and inequities that are systemic in the global health workforce where women health workers are concentrated into lower status (only 25% of health leadership roles are held by women), lower paid and often, unpaid roles and are facing harsh realities of gender bias and harassment.

Figure 2: Distribution of physicians and nurses by gender in regions around the world — licence infos

Women are also the majority of service staff in healthcare and social care facilities, such as nursing homes, who clean, serve food or do laundry. And women’s underpaid care work is predominantly relied upon to serve as home health or personal care aids in many countries globally, for example for elderly or disabled people. Women working in these fields often lack access to health insurance or social protection such as paid or sick leave. This is the case for many women migrant workers, such as many Polish home health aides supporting families in Germany. This is also the case for the 86% of home health care aids in the United States that are women, of which African American women and Latinas make up 59%, thus showcasing the intersectionality with race, ethnicity, immigration status and geography of the health and social work wage gaps experienced by women.

As a result of this segregation and those corresponding social and economic fault lines, women in the health care and social care sectors, and thus a disproportionately large share of women of color and migrant women, are at the front lines of caring for COVID-19 patients and working to prevent widespread community infections. In China’s Hubei Province, about 90% of health care workers battling the coronavirus were women. In the United States, in early April the global epicenter of the pandemic, the percentage of female health care workers is around 78%.

Due to the type of work that female health and social care workers are predominantly doing, which involves more intimate and direct physical contact with those they care for in roles like phlebotomists or nursing-home aides that not coincidentally are also at the lower end of the health care worker payscale, women are at increased risk of exposure to the virus and infection. This is made worse by the fact that personal protective equipment (PPE) such as surgical gowns, gloves and masks is provided in insufficient numbers to many health care and social workers and especially to those considered to be in positions of lower status in the health care and social sectors. Additionally, gowns, masks and shields are often “default-sized” for males and thus ill-fitting for many women. A gender-differentiated look at the number of healthcare workers infected with the COVID-19 in Spain and Italy, the two European countries most severely affected, confirms the dangers for women health care providers. While in late March in Italy 66% of the health care workers infected were women, the number in Spain was even higher at 72%.

With women health and social care workers already facing higher infection rates and thus danger to their physical well being, the efforts on the front-lines of the fight against the coronavirus have also revealed how little attention is paid to the psychosocial and even sanitary needs of these women workers. There are reports from China that menstrual hygiene products such as sanitary pads or tampons were not provided to female caregivers and front line responders as part of their PPE, even though UN Women and other organizations stress that the provision of such personal hygiene items is essential for the health and dignity of female health workers as well as for women and girls quarantined for prevention, screening and treatment. Some first studies have also found particularly high rates of depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress among the female nurses and health care professionals dealing with COVID-19 in China, which some researchers explain with findings suggesting that women are stronger at emphasizing than men. Virtual mental health apps, such as Headspace or Talkspace, which connect users with licensed therapists, have seen their volume of users increase significantly over the past weeks.

Initial data indicates that this growth comes largely from female healthcare professionals explicitly citing the stress of their work to contain the pandemic as their reason for seeking assistance. The psychosocial burden on top of the physical comes because women in healthcare and social care professions are expected to also perform high levels of emotional labor as nurses and counselors. There is also the societal expectation and pressure that women are the more “natural” caregivers, emotional support providers and multitaskers – not just at their paid jobs, but also as the main healthcare logistical support unit for their families. Thus, many female health and social care professionals do double duty in caring: often underpaid at their job and entirely unpaid at home.

B. Unpaid Care Work

Even before COVID-19 became a pandemic, women and girls around the world already routinely did most of the unpaid care work at an economic value estimated by UN Women to be $11 trillion, without which societies – and the global economic system – could not be sustained. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), women perform nearly three times as much unpaid care work as men, or 76.2% of all total hours of unpaid care work, which in some regions, such as Asia-Pacific, reaches even 80%. While in some countries, men’s contribution to unpaid care work has increased over the past 20 years, the pace of improvement is glacial at best and the ‘male breadwinner’ family model remains deeply ingrained within societies. This is a result of sticky cultural and social roles and norms and expression of male entitlement in many countries, often combined with practicalities such as more job flexibility and economic necessities as women dominate in informal, part-time, and low-wage jobs. However, studies indicate that even when women out-earn their husbands or the husband is unemployed, women continue to do more of the household chores. Experts have calculated that at the current rate of improvement, it would take 210 years to close the gender gap in unpaid care work.

Uncompensated and underappreciated care needs have increased exponentially with the pandemic and with it also the dangers of exposure to the virus within families. As schools and daycare centers are mostly closed the responsibility for in-home child care still falls predominantly to women; more people forced to stay at home has also increased demand for household chores; and women who traditionally serve as the caretaker for older and sick people within families are called upon especially in times when public health and social care services are overwhelmed as more in-home care work is needed. Caring for sick family members at home in particular also increases the health risks for females as the primary caretakers, and most so in developing countries with weak health systems. This was also the experience of the Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa, where women not only cared for the sick at home, but also traditionally prepared bodies for burial. Studies indicated that in the case of Ebola for example, the transmission rate was higher in households than in hospitals. And it is still unclear to what extent women’s unpaid care work will be relied upon as family and community healthcare workers in the immediate aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the long-term care needs of communities and individuals surviving the coronavirus are not yet known. If the Zika epidemic is any indication, those future demands could be immense. Post-Zika outbreak, it is largely women performing routine vector-control activities in their communities; many women were also unable to return to their paid jobs and are caring instead for children born with Congenital Zika Syndrome in the absence of public support systems.

Nothing illustrates the call to mostly women to step up their unpaid care taking, not just at home, but also for the benefit for the wider community during the pandemic, then the recent surge in the sewing of face masks at home, as the lack of formal protective face gear in many countries – for paid caretakers as well as unpaid ones in families and to enforce social distancing for everyone – has led to a call for community solidarity. In response, mostly women are hunching over sewing machines or hand sewing at home or even in refugee camps to make masks for their families and nursing staff free of charge. This, while a great expression of social support, once again relies on the work of mostly women to compensate for the lack of preparation and provision by authorities, adding to women’s already existing mental and physical care burden and stress during the time of crisis, as many women feel pressured to contribute.

Increased care burdens in times of coronavirus are especially hard for formal sector female employees with children trying to juggle child care, elder care, homeschooling and housework simultaneously. This is happening even though more fathers are “stepping up” their unpaid care contributions (and receiving praise and acknowledgement for what should be a matter of fairness within families) while staying at and working from home, although this is by far not universal. Managing the increased care demands is nearly impossible for female headed households, who are especially vulnerable during the pandemic. In the UK, a quarter of all families are headed by a single parent, more than 90% of which are women. In the United States, for example, 41% of mothers are the sole or primary breadwinners in their families despite earning just 69% of the income of male breadwinners.

Government responses in bailout and stimulus packages must therefore include social protection measures reflective of and recognizing women’s disproportionately high contribution to the care economy, such as affordable health insurance with benefits, emergency cash assistance, and paid sick leave and family medical leave for those unable to come to work because they are taking care of children or elders at home. At the same time, government messaging, official communications and risk mitigation strategies need to actively promote a gender-equal sharing of the care work involved in surviving the current crisis at the individual and household level. Only then can the crisis also be an opportunity to speed up the erosion of social norms and entrenched practices that have led to the still prevailing lopsided distribution of unpaid care work within households, families and communities.

C. Healthcare Governance and Decision Making

While women do the brunt of the work in health and social care globally and face greater risks, men make the global healthcare decisions: 69% of global health organizations are headed by men, and 80% of board chairs are men, with only 20% of global health organizations having gender parity on their boards, and only 25% having gender parity at the senior management level.

This is despite the experience from previous health emergencies such as Ebola or Zika that showed that by not incorporating women’s voices and experiences and gender expertise into response measures, the effectiveness of overall health interventions were undermined and women’s and girls’ specific health needs were largely unmet.

Unfortunately, this pattern of gender blindness in global health governance also continues to hold for the various task forces and agencies dealing with the response to the coronavirus pandemic at the national and international levels, where women are substantially underrepresented, and gender expertise is largely absent. The WHO Emergency Committee on COVID-19 is only 20% female, despite the WHO’s own recently approved Executive Board decision on strengthening preparedness for health emergencies, which urges member states to “take action to engage and involve women in all stages of preparedness processes, including in decision-making, and mainstream gender perspective in preparedness planning and emergency response.” The message has yet to reach many countries. Take the United States for example: even after a second round of restructuring, only 10% of the members of the U.S. Coronavirus Task Force are women. The group was initially set up only with men, inviting criticism of a “mandemic” response. UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s lead team for the UK’s COVID-19 response is likewise all men.

The resulting lack of integrating women’s voices and experiences as well as a lack of gender expertise in outbreak response and post-pandemic recovery is worrisome. Going forward all COVID-19 response planning and decision-making should be inclusive, not only equally representing men and women, but also prioritizing racial and ethnic diversity. Including gender-responsive and intersectional analysis and methods in public health, crisis economics, technology and risk communication is crucial for building preparedness and resilience for this and future emergencies and disasters, such as in the health or climate arena.

D. School Closures and Impacts on Education

As of early April, the COVID-19 pandemic has forced school closures in 192 countries according to UNESCO. Now, 91% of enrolled students globally (or 1.57 billion children and adolescents) are at home, with the likely result that the already existing learning gap between the rich and the poor will grow further, both between high and low-income countries as well as within countries between high- and low-income regions, communities, and neighborhoods.

While school closures will disrupt education for all children, and particularly those from disadvantaged countries and communities, UNESCO and other experts are warning that these school closures are likely to hit girls hardest and with the most lasting effects. For one, in many countries school closings increase the care work burden of both women and especially older girls, such as for home schooling and providing child care for younger children. Already before the pandemic, adolescent girls spent significantly more time on chores in comparison to boys and thus had less time for their education. If experience from past epidemics and times of economic hardships is any guide, in numerous developing countries – many requiring school fees, particularly for secondary education – adolescent girls are also more likely to drop out of school and not return even after the end of the crisis. This is often because they are pushed to contribute to income generation as families consider the financial and opportunity costs of educating their daughters at times of growing poverty and in societies lacking social safety nets. In many instances in these situations, adolescent girls are married off early; sexual exploitation of girls often also increases outside of the protection offered by schools, including as a result of selling sex for food and other essentials while families struggling to cover basic needs. During the Ebola crisis, adolescent pregnancy increased by up to 65% in Sierra Leone, with many pregnant girls never returning to the classroom, as Sierra Leone just recently revoked a policy preventing pregnant girls from attending schools. Even if not prohibited per policy, pregnant teens and young mothers often face discrimination and stigma that prevent them from returning to finish their education, with adequate support services lacking in many countries, including in industrialized, richer nations.

With distance learning as a result of pandemic related school closures in many countries moving increasingly online, it is important to also recognize the existing digital divide among students quarantined at home, in which gender intersects with class and income level, race or geography, as illustrated by the findings of a recent analysis looking at differences in distance learning based on countries’ income levels.

In many households, where multiple family members need access to limited online resources in the home, gender inequality could restrict girls’ access. Targeted efforts by some US school districts to send children into the forced corona break with laptops are laudable, they are not feasible for poorer school systems in the United States, let alone in many developing countries, and do not address the fact that many families and communities are left behind by digitalization. Thus, low-tech and gender-responsive approaches, including written materials or local radio and television broadcasts might be needed to reach the most marginalized and poorest students with flexible learning schedules to accommodate girls’ care chores at home as an alternative to learning via the internet. School closures also mean that girls and the most vulnerable youth miss out on support services usually provided via schools, such as school meals, social protection or counseling. Maintaining school feeding programs (which alone in the United States support 30 million US children from low-income families) and other services as best as possible or finding alternative ways to deliver support such as food rations or teaching support may make the difference of whether the most disadvantaged children, including many girls, can keep up with and their education during and fully resume schooling after the pandemic.

V. Gendered Health Implications

The corona crisis is showing clear gender-differentiated health and personal safety impacts, making it crucially important to ensure the collection of sex-disaggregated health data to learn gender-specific lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and to apply them to future global health crises. The opportunity to do so has been largely ignored following the SARS or Ebola epidemics over the past decade to prepare for future outbreaks then, but this is a key imperative for how health systems around the world are addressing and monitoring the pandemic now.

Much has been made over the emerging data first from China and then largely replicated in Europe, the United States and other countries that men, while roughly infected at the same rate as women, seem to suffer from disproportionally more severe symptoms of COVID-19 and have much higher fatality rates as a results, from 10% higher to twice as high as observed in Italy. Both biological (genetic and hormonal differences based on sex) and social and cultural (gender roles) factors are suspected among the reasons, but health researchers also acknowledge that further study is needed. In that sense, the COVID-2019 pandemic might provide the much needed wake-up call to global health researchers to analyze their studies’ results by sex or to perform experiments for example on the effectiveness of new medications on both male and female models. In epidemiology, the fact that women often have lower survival rates from much studied conditions such as heart attacks or often experience worse side effects from approved medications than men can be blamed on such gender-blind approaches.

However, sex-disaggregated data collection, while important, is not enough, as the sex-differentiated susceptibility to and morbitity from COVID-19 is compounded by other factors. These strongly showcase the importance of acknowledging the intersectionality of gender with race, age, class, or, as COVID-19 in the global context has made glaringly obvious, geography. For example, it is important to acknowledge the specific health threats and health situation of indigenous women as indigenous communities already experiencing poor access to healthcare, significantly higher rates of communicable and non-communicable diseases, lack of access to essential services, sanitation, and other key preventive measures with significant impacts on their vulnerability to the virus. Gender differences within indigenous communities are also compounded by different traditional gender roles.

While age has been identified as the core determinant for the severity and death rates from COVID-19, in the United States for example, the reckoning is only just beginning with the fact that black communities, but also Latinx neighborhoods such as in New York City in early April, see much higher risk of COVID-19 infections and have more severe outcomes than white neighborhoods, and thus African American women and Latinas more so than white ones. This is compounded by the lack of comprehensive data on race as a factor for COVID-19 outcomes collected by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Although the higher rates of underlying health conditions such as obesity or diabetes in black communities might be partly to blame, this is compounded by what physicians in public health and on the front lines see as an unfortunate repetition of familiar patterns of racial and economic bias in the response to the pandemic, for example with respect to the access to coronavirus testing. Those systemic discriminations and biases in the US health, social and economic system are also at least part of the reason why black women are twice as likely to die in childbirth as white women. Thus, the pathology of COVID-19 is worsened by the pathology of persistent American racism.

With inequities in access to health care during the COVID-19 pandemic already significant within countries, in most developing countries those inequities are exponentially magnified. Not only recognizing those but addressing immediate needs while avoiding and repairing past harms done is for many gender and human rights groups part of a necessary feminist response to COVID-19 and an urgent matter of global justice. Scores of countries in the Global South are facing the pandemic with severely under-resourced and weakened public health systems, which in many developing countries have suffered from multiple rounds of austerity mandated by IMF and World Bank loan and bailout programs since the 2008 financial crisis and relentless privatization efforts. By some estimates, only half of the world’s population is able to access essential health care services even in non-pandemic times. The Southern African’s People’s Solidarity Network warns that in Southern Africa public health systems, on which the majority of people depend, are already on their knees even before COVID-19 has fully hit, with Zimbabwe only having 20 ventilators country-wide or Malawi having just 25 intensive care unit beds for a population of 17 million people. In other parts of the world, the situation is similarly dire, such as in Afghanistan where the war-torn, highly rural country of 31.6 million people only has isolation centers with 1,100 beds operational nation-wide. It is often an informalized system of home healthcare and unpaid community health work for the sick, elderly and children built on the backs of women that is providing the back-up for the precarious state of public health systems in many of the poorest developing countries.

A. Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Concerns and Rights Curtailed

Apart from the direct impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic in terms of infection and death rates, women’s health, and especially their sexual and reproductive health, needs, and concerns are also negatively affected by the global health crisis. Their sexual and reproductive rights in many instances are also severely curtailed. The gendered impacts of disease outbreaks such as the Ebola virus or the mosquito-borne Zika virus have been documented, including by human rights groups and gender advocates, who demand that lessons from these previous epidemics should be applied by governments and international bodies so as to closely monitor the impacts of the pandemic on the rights of women and girls to access sexual and reproductive health services and intervene in a timely and proactive manner to protect them.

At the health system level, the prioritization of and diversion of financial resources to COVID-19 responses could take funding away from reproductive health programs and decrease access for women who rely on free or subsidized services for such care. Worldwide more than 214 million women and girls of reproductive age have no access to modern contraception to prevent unwanted pregnancies. As an immediate result of the pandemic, an additional 9.5 million women and girls could lose access to family planning services they previously enjoyed. Shortages of medications, such as contraceptives, raw materials such as progesterone, or antibiotics to treat sexually transmitted diseases are also likely with disruptions in supply chains, especially from China, the second-largest exporter of pharmaceutical products globally, and India, a significant manufacturer of generic medicines. One of the largest providers of family planning products in the world is already reporting or anticipating shortages of family planning devices in several countries, for example of contraceptive implants in Myanmar or condoms in Mozambique.

The time-sensitive access to abortions as essential healthcare and manifestation of women’s sexual and reproductive rights – already severely restricted in many countries in normal circumstances – has been further complicated by many countries and national jurisdictions declaring abortion services as “non-essential” and outright forbidding the medical procedure during the COVID-19 pandemic, including many countries in Europe such as in Poland, Ireland or Italy. In the Unites States for example, five states – Ohio, Texas, Iowa, Alabama and Oklahoma—have used emergency declarations to temporarily ban abortions during the coronavirus outbreak, with 18 other US states contemplating similar measures, despite American medical associations warning that delaying the procedures in many cases will be tantamount to denying it. There is also growing concern that restrictions on access to abortion imposed in the time of the coronavirus crisis will be continuedafter the pandemic. Even where still allowed, scheduling the procedures for many women in many countries has become more difficult as a consequence of less capacity and limited supplies and social distancing requirements. Women’s health advocates stress that the COVID-19 pandemic thus highlights the necessity of destigmatizing abortion globally, including by increasing accessibility to self-managed medicational abortions. It also highlights the need to continue the fight against restrictions placed on health care service provision that might include abortion procedures through official development assistance (ODA), such as not allowing international aid to be used for abortions, which hampers the ability of nongovernmental organizations abroad to fill in the gaps in sexual and reproductive health services created by the COVID-19 response and in preventing and containing an outbreak, for example in humanitarian responses to displacement and the refugee crisis.

Increased pressure on health systems and a diversion of resources in many countries during the corona crisis also reduces the availability and access to standard gynecological examinations and preventive care, such as pelvic exams, or prenatal and postnatal care for many women. The latter is particularly dangerous, as pregnancies,birth, and the need to breastfeed do not pause in pandemics. This could have significant lasting repercussions for mothers and their infants born during the pandemic beyond the actual health threat of COVID-19, as data on the rise of maternal mortality in the region affected by Ebola or on inadequate access to postnatal and infant health care during the Zika virus outbreak illustrates. While the limited data currently available seems to suggest that COVID-19 does not pose a health threat for pregnant women and their unborn children (contrary to vector-borne Zika for example) and should not prevent nursing, the World Health Organization admits that much more targeted research needs to be done to rule risks out conclusively and warns that pregnancy in general might increase women’s susceptibility to some respiratory infections. Experts say this requires an enhanced focus on primary prevention for pregnant women.

Due to the strain on health systems and clinics, more expectant mothers and their families have considered at-home-births – which is already the only option that numerous women in developing countries have. This is not suitable for higher risk pregnancies, and should be a choice for women, not a de facto necessity due to deteriorating health conditions. In several countries, including Germany and the United States, individual hospitals have also resorted to barring partners and visitors during childbirth, thus disregarding the WHO guidance which reminds all parties that pregnant people, irrespective of infection status, have the right to high quality care before, during and after childbirth, and that this includes being treated with respect and dignity and having a companion of choice present during delivery. After birth, all new mothers, regardless of infection status, should be encouraged and supported to breastfeed, with special attention also paid to signs of postnatal anxiety and depression, which could be exacerbated during the pandemic by the social isolation and financial impact on the family and wider community, as the UN Population Fund warns.

B. Health Concerns and Sexual Rights of LGBTI and Gender Nonconforming People

The impacts of COVID-19 on health and sexual rights are also felt acutely by lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex people (LGBTI), and gender non-confirming people (GNC), who are often among the most marginalized and vulnerable population groups in many countries. Even before the pandemic, these individuals were facing multiple and intersecting forms of discrimination such as homophobia, bias and criminalization and prosecution, as well as barriers in access to healthcare and related services. As a result many LGBTI and GNC people already suffering from conditions such as obesity, heart disease, respiratory problems or compromised immune systems from chronic diseases such as asthma or HIV are now also among those groups at higher risks for severe COVID-19 outcomes. Transgender and intersex individuals, who may have particular health needs such as hormonal treatments or gender-affirming surgeries during the coronavirus crisis, might find those interventions postponed or canceled in many countries around the world such as in Thailand or Spain, as medical systems consider them non-essential. The growing uncertainties over when such services might resume could aggravate mental health issues, including depression, anxiety and suicidal thoughts, from which a disproportionate number of LGBTI and GNC individuals are already suffering.

VI. Gendered Safety and Security Implications

The coronavirus crisis has grave repercussions for women’s personal and communal safety and security, whether it is the increased risk of gender-based violence, the changing threat of human trafficking, or the increased humanitarian safety needs and protections required added to those already caused by conflicts, flight or displacements. While women and girls have suffered from these brutal forms of violence even before the COVID-19 crisis, the already severe impacts of these forms of violence are now exacerbated by the pandemic at a time when resources and attention to address them are often diverted or prioritized for other response measures.

A. The Shadow Pandemic of Gender-Based Violence and Domestic Violence